As one might expect of a census, the book provides a minutia of facts. For example, 1,525 quarries operated and generated 115,380,133 cubic feet of stone, roughly enough to build one and a half Great Pyramids. Or you can learn that a David Williams owned a slate quarry in Slatington, Pennsylvania. The quarry was in Lower Silurian beds, produced black slate for roofing and school slates, and opened in 1864. Sounds like an industrious fellow.

Of more interest is the section that describes the building stones used in 137 cities, ranging from Akron, Ohio to Zanesville, Ohio. The listings reveal the classic story of most cities and towns, which generally use local stone, if available. Some people also import outside rock, most often for monumental buildings such as banks or churches. The story changes slightly in the bigger cities of Boston and New York, which still use local rock but also pull in stone from around the world. For example, exotic marbles came from Italy, France, Portugal, Switzerland, Spain, and Germany. That being said, 80 percent of the stone fronted houses in New York City used brownstone, most likely quarried in either Connecticut or New Jersey.

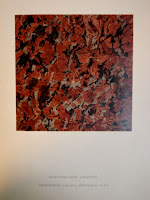

A hornblende granite from Grindstone Island in New York, some of which was used as paving material in Chicago

Reading through the census book, I am reminded of other books like this. These are the older scientific books that seemingly attempt to put in everything known about a subject. They are clearly labors of love of the writer and detail not just the science but also the history of a subject, such as the origin of a name of a species or who first used a particular building stone. In delving so deeply into the finer points, the authors make their subjects so interesting that the reader cannot help but take a deeper interest.