With the inauguration of Barack Obama as president, another milestone has been passed: the first president to graduate from high school in Hawaii. To honor that rather trivial tidbit, I will consider a short-lived facet of the Aloha State’s educational past, which of course has a connection to stone. Prior to the arrival of missionaries in 1820, native Hawaiians did not have a written language. Soon after landing, missionary Hiram Bingham (grandfather of the Hiram Bingham who rediscovered Machu Pichu) and others began to develop an alphabet in order to teach Hawaiians the Bible.

One key aspect of teaching involved writing out the language, which was done on small school slates that the missionaries had brought with them. Such teaching implements, often consisting of a small slab of slate surrounded by a wooden border, had been been used for hundreds of years in Europe and were starting to become more widespread in America in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Since slate was not what one would call abundant in the Hawaiian islands and throughout the South Pacific, other missionaries report that students used flakes of rocks and dyed them purple with plants juices “to give them the appearance of English slates.”

Educators faced one more problem: how to write on the slate. Chalk was not available so again the missionaries relied on local resources. John Williams a missionary to the Cook Islands wrote in his memoir:

“The next desideratum was a pencil, and for this they (the students) went into the sea, and procured a number of the echinus, or sea-egg, which is armed with twenty or thirty spines. These they burnt slightly to render them soft that they might not scratch; and with these flakes of stone for a slate, and the spine of the sea-egg for a pencil, they wrote exceedingly well.”

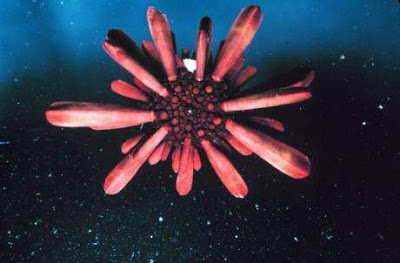

For those of you not familiar with the sea-egg, we know it better as a sea urchin. Specifically the species is Heterocentrotus mamillatus, the slate-pencil sea urchin. Its spines can be up to 10 cm long and weigh over 5 grams. They are made of calcite. Like the spines of all sea urchins, they are used for gathering and manipulating food, defense, movement, and for holding tight in cracks. When broken or removed, the spines regenerate, which takes many months. In modern times, these spines show up in wind chimes. Historically, native peoples used the spines as files to make bone and shell fishhooks, though one researcher reported that in Micronesia some people used two spines like chopsticks to pluck up pubic hairs. He did not elaborate and nor can I.