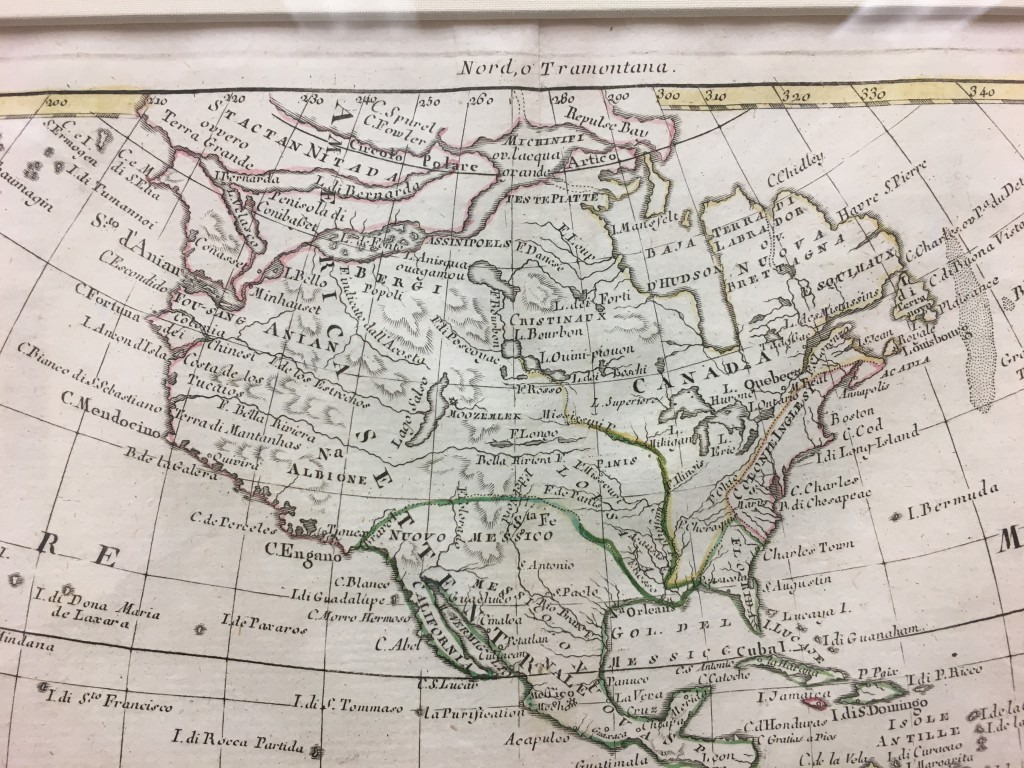

In my previous post, I mentioned how Apostolos Valerianos sailed north to about 47 degrees latitude. His goal at the time was a shortcut between Asia and North America, which mapmakers had started to place on maps in the middle 1500s. Known as the Straits of Anian, it would cut off thousands of miles of sailing by allowing ships to travel directly across North America instead of south around South America.

During his conversation with Lok, Valerianos said that he had taken his ships into the Straits and sailed for more than twenty days, finding a land rich in gold, silver, and pearls. He then returned to Mexico, where he had started, where he reported he had “done the thing which he as sent to doe.”

Coincidentally, I was at Seattle Pacific University yesterday in the Ames Library and came across a map from 1770. It was created by Venetian cartographer Antonio Zatta. As you can see, there is no Puget Sound nor even a Strait of Juan de Fuca. Instead Zatta depicts the Strait of Anian, which providentially connects via a river and a small lake north to a much larger lake that in turn allows one to continue east to another body of water and finally out it to Hudson’s Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. And if that wasn’t good enough, note the Bella Riviera, which stretches across almost the entire continent. If only the landscape conformed to the imaginations of cartographers.