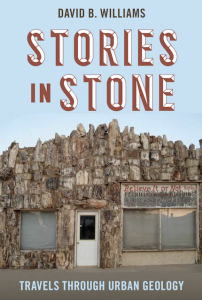

***BUY NOW FROM ME.***

($30 – includes shipping and signature. Link goes to a Square payment site. Shipments only in U.S.

WANT THE ORIGINAL HARDBACK. I HAVE A FEW LEFT.

LIMITED TIME OFFER

($15 – includes shipping and signature. Link goes to a Square payment site. Shipments only in U.S.)

In this age of concrete and titanium, it may seem anachronistic to look at building stone. But for centuries, stone was the material of choice, and it is still the chosen material for this country’s most elegant structures. Reasonably fireproof, infinitely colored, and often readily available, stone allows for larger buildings than wood and, with a few notable exceptions, retains its structural integrity for thousands of years. Knowing that a building’s success or failure often rests on the choice of stone, architects and builders continue to comb the globe, from the fjords of Scandinavia to the deserts of South Africa, searching for the perfect rock for their structures.

Why is stone so bewitching? Well, for one, it’s alive—a living, breathing material that changes gracefully over time. Second, it is natural—people may not know the stone’s origins but they intuitively sense the link between stone and the world around them. And third, no two stones are exactly alike, every structure has a unique look, feel, and story.

But there’s more to it than that. Within every stone structure is a story of geological origins that goes back to our earth’s creation. As a self-described geo-geek, I pride myself on being able to unlock these stories.

In Stories in Stone, I braided together natural and cultural history to explore the untold life of building stone. The project grew out of my 20-year passion for geology and desire to strengthen my bonds to nature. Each chapter focuses on a particular type of rock and describe my search to learn more about the stone, the particular building or building style that exemplifies its use, and the people involved in construction. Along the way I interviewed geologists, explored quarries, and consulted with preservationists and historians in order to give readers greater insight into these structures.

By telling the stories of stone from formation to foundation, I tried to open a new window for viewing the urban landscape. I wanted to show that intriguing natural and cultural history stories are no further than the nearest building. I hope that Stories in Stone will encourage people to look more carefully at the natural world around them, ask more questions, and go outside and investigate.

In fall 2010, Stories in Stone was named a finalist for the 2010 Washington State Book Award in the general non-fiction category. I think that’s pretty cool and and a great honor to be in such august company with the other finalists and winner.

Ch 1 Most Hideous Stone Ever Quarried – Brownstones of New York – Formed by streams that deposited sand into a vast valley formed during the breakup of Pangaea and the opening of the Atlantic ocean, the rust-colored sandstone is known by many as brownstone. During the late nineteenth century it was the ubiquitous building stone of rowhouses in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. The stone was so popular that James Flood shipped tons of it around Cape Horn to build his house in San Francisco.

Ch 2 The Granite City – Quincy Granite and Bunker Hill Monument – The construction of the Bunker Hill Monument led to the first commercial railroad in the country. It also jump started the granite industry and Quincy, Massachusetts, and made granite the key building stone of the eastern seaboard during the middle 1800s.

Ch 3 Poetry in Rocks – Robinson Jeffers’s Tor House Granodiorte – Robinson Jeffers, one of the great American poets of the mid-twentieth century, exemplifies the direct connection between people and stone. As he wrote, “My fingers had the art to make stone love stone.” His intimate knowledge of rocks came from the years he spent finding, carrying, and placing boulders he collected from the beach near the house he built in Carmel, California.

Ch 4 Deep Time in Minnesota – 3.5 billion year old Morton Gneiss – The 3.5-billion-year old Morton Gneiss is the oldest commonly used building stone in the world. With its beautiful pattern of swirling pink and black, the Morton Gneiss provided a vibrancy that contrasted and complicated the geometric shapes of Art Deco architecture.

Ch 5 The Clam that Changed the World – Castillo de San Marcos and Coquina – Built between 1672 and 1696, the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, is the oldest fort in the United States. It is made with one of the youngest building stones in the trade, a 110,000-year-old rock known as coquina.

Ch 6 America’s Building Stone – Salem Limestone – Go to any city across the country and you will find one building stone in all of them: Salem Limestone from Indiana. It is the most popular building stone in the country. Rich in fossils, it formed 330 million years ago when a tropical sea covered most of the central United States.

Ch 7 Pop Rocks, Petroleum, and Petrified Wood – Lamar, Colorado’s petrified wood gas station – One of the most unusual building stones and buildings is a small gas station in eastern Colorado made from petrified wood. When built in 1932 by the man who later invented Pop Rocks candy, the station attracted the attention of Ripley’s Believe it or Not! and of Frank Phillips, founder of Phillips Petroleum.

Ch 8 The Trouble with Michelangelo’s Marble – Carrara marble in Chicago – Michelangelo carved David out of Carrara marble 500 years ago and he still looks good. Standard Oil covered their world headquarters in the same marble; the panels didn’t last 19 years. No one had accounted for harsh weather destroying what is arguably the most famous stone in the world.

Ch 9 Reading, Writing, and Roofing – Vermont Slate is everywhere – Slate is one of the most versatile stones. In addition to serving as a medium of communication, including as school-slates and pencils, slate has been used for electrical panels, steps, flagging stones, billiard tables, and gravestones. It carves easily, separates into layers easily, requires little maintenance, and comes in a variety of colors. Its greatest use in the building trade has been in roofing.

Ch 10 Autumn 80,000 Years Ago – Italian travertine, the Getty Center, and the Colosseum – Richard Meier examined stones from around the world before he chose an Italian travertine for his monumental Getty Center in Los Angeles. He was continuing a long tradition for this stone, which was first used by the Romans 2,000 years ago for buildings such as the Colosseum, and is still one of the most used stones in the trade.

Stories was originally published by Walker and Company in 2009.

“We live in the Stone Age. In this delightful book David Williams points out that one needn’t travel to wild places such as Yosemite or the Grand Canyon to geology—geology is in our cities in the stones used to construct our homes, schools, government buildings, and other other structures…I enjoyed this book both time when I read it.”

~ Journal of Geoscience Education — 2013

“I admire the cleverness of Williams’s device, but it would have failed were he not such a fine storyteller…His explanation of why Carrara marble proved to be an unfortunate choice for cladding Standard Oil’s Chicago headquarters is unusually clear and yet lyrical. What else would you expect from a science observer who includes a visit to Robinson Jeffers’s (granite) Hawk Tower in his book on rocks?”

~ American Scientist — January/February 2010

“Author David B. Williams makes a compelling case to look closer at a building’s very stones…Although Williams does an admirable job of explaining where to find the stones and how they formed, the book really shines when he talks about the human connections—how the stone is quarried by people and added to buildings under conditions that reflect unique historical circumstances.”

~ Earth – October 2009

“Cities may seem like the most artificial places on Earth, yet a close look at massive buildings can reveal troves of natural geological glory. In chapter after fascinating chapter of Stories in Stone, Williams…deftly describes the mineralogy and history of some of the world’s most common building materials…[T]his book reveals that natural and cultural history may lie no farther than the building next door.”

~ Science News – September 26, 2009

“Geologist Williams takes the study of “urban nature” in a new and pleasurable direction by conducting a geological survey of the stones used in city buildings…From stony metaphors to the sculptures of Michelangelo, architectural breakthroughs, and geology’s role in the evolution debates, Williams’ record of human dreams worked in stone is as richly textured and full of life’s imprints as a fossil-rich piece of travertine, the stone used on the facade of the magnificent Getty Center in Los Angeles.”

~ Booklist – July 1, 2009

“The book is filled with terrific information, and a whole new way to look at a city, and the world. … The book, altogether, is truly brilliant — as idea, and execution.”

~ William Wallace

Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History

Washington University

“Stone buildings are symbols of urban denaturation, but in this engaging popgeology excavation, Williams sees them as biological entities. … While telling these sagas, the author investigates the science of rock dating and techniques of quarrying, recounts the exploits of great geologists and the travails Michelangelo faced in transporting marble blocks from the quarry to his workshop, and ponders the often surprising structural and aesthetic character of different species of stone. (The coquina stone of St. Augustine’s fortress is material for stopping cannonballs, even though it’s as fragile as a Rice Krispies Treat.) Williams’s lively mixture of hard science and piquant lore is sure to fire readers’ curiosity about the built environment around us.”

~ Publishers Weekly – May 3, 2009

“Stone speaks volumes with great beauty, the author avers. Having studied geology in college, Williams spent some years in the rapturous geologic landscape of Utah before moving to Boston. He was starved for his geologic fix until he realized that he was surrounded by stone. With giddy infectiousness, he launches into the cultural geology of various rock types. … He does a yeoman’s job linking Robinson Jeffers’ love of stone to his poetry—its strong, supple metaphorical associations, its lasting value. … Each line of inquiry coaxes out some expressive scientific, emotional or philosophical nugget from a piece of travertine, slate or, in one Pop Art extravaganza, a gas station made of petrified wood. Makes stone sing.”

~ Kirkus Reviews- May 1, 2009

2 thoughts on “Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology”

Comments are closed.