Bertha the Tunnel Boring Machine and her travails got me thinking about Seattle’s long history of tunneling and tunnel plans. In an article by Red Robinson, Edward Cox, and Martin Dirks, the authors wrote that over the past century or so, “more than 100 tunnels totalling over 40 miles” have been excavated in Seattle. These include sewers, railroads, water lines, landslide stabilization, and busses. The earliest dates back to the 1880s.

What they don’t mention are the numerous tunnels proposed but never built including ones under First Hill, Denny Hill, and Beacon Hill.

Here is a very short list of some of those that were built and those that merely were dreams.

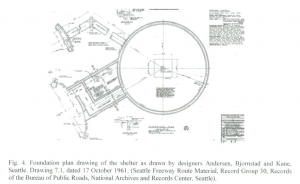

1. Great Northern Tunnel – 1903-1905 – The 5,141-foot-long tunnel allowed trains to bypass Railroad Avenue and drop passengers at the Great Northern’s new Union Depot (later called King Street Station), being built out into the tidelands at the south end of downtown. The tunnel was built from either end, into the center. The crews met on October 26, 1904, Along the way, they had encountered a forest of buried trees. They also had a few troubles, including buildings settling as the tunnel went beneath them, which prompted a simple solution. When the York Hotel (also known as the Ripley) was damaged the Great Northern simply bought it and leveled it thus eliminating the problem. Seattleites liked to joke that it was the longest tunnel in the world as it went from Virginia to Washington…streets.

2. North Trunk Sewer -1908-1914 – Prompted by a fears of cholera and typhoid, the city built almost 22 miles of sewer tunnel, mostly in the north end, including one of the longest sections, the 3,500 foot tunnel under Ravenna Creek from its former outlet at Green Lake to the University Village. Workers started with a shielded boring machine (an early predecessor of Bertha) but it was not able to cope with the soil conditions so ultimately the tunnel was dug by hand. The tunnel failed in Novembr 1957, creating a massive sinkhole at 16th Ave. N. and NE Ravenna Boulevard.

Tunnels that never made it.

1. Denny Hill Tunnel – 1890 – L.H. Griffiths, developer of Fremont, proposed a tunnel under Denny Hill to make it easier to reach his development. It was stopped though several years later, Thomas Burke, a leading opponent of the tunnel, suggested it should have been built.

2. Jackson Hill Tunnel – 1904 –In early 1904, residents requested the city to excavate a tunnel through Jackson from Fifth to Twelth avenues. After a careful investigation, city engineer R.H. Thomson rejected the idea and convinced proponents that it would be better to eliminate the high ridge, which was done during the Jackson Street Regrade.

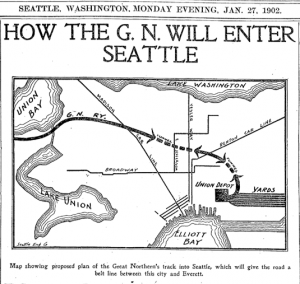

3. Beacon Hill – 1902 – Great Northern proposes to enter Seattle by tunneling under Beacon Hill. Work was started and went several hundred feet before stopping.

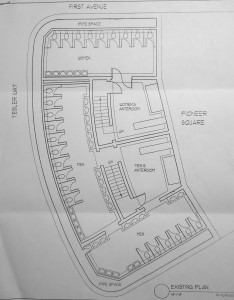

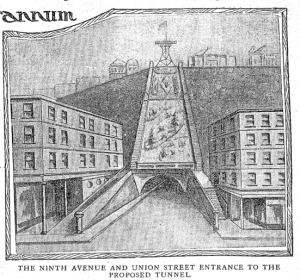

4. First Hill – 1903, 1908, and 1929 – Various groups over the years proposed tunneling under First Hill to access the valley beyond and also to access Second Hill.

5. Bogue Tunnels – In 1911, engineer Virgil Bogue presented a grand transportation and city plan for Seattle. His proposed tunnels included Day Street in southeast Seattle, and ones under parts of First Hill, West Seattle, Interlaken, Spokane Street, and Blanchard Street, as well as railroad tunnels under Beacon Hill, Wedgwood/View Ridge, and downtown Seattle.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.