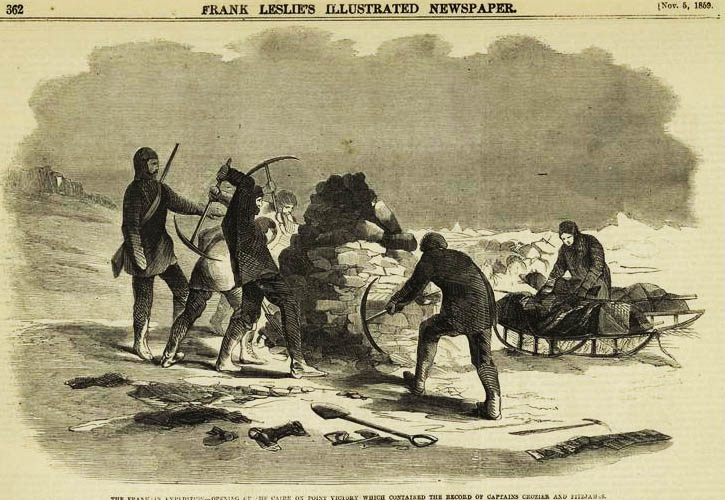

One of the world’s most famous cairns was located almost exactly 143 years ago on May 5, 1859. On that day, William Hobson and a team of men located a mound of sandstone blocks frozen on the northwest coast of King William Island in Canada. When the men dismantled the ice-crusted cairn, they found a sealed copper cylinder holding a single piece of paper. The document had been written by James Fitzjames, the captain of the Erebus, one of two ships along with the Terror from the fabled John Franklin Expedition, which had left England in 1845.

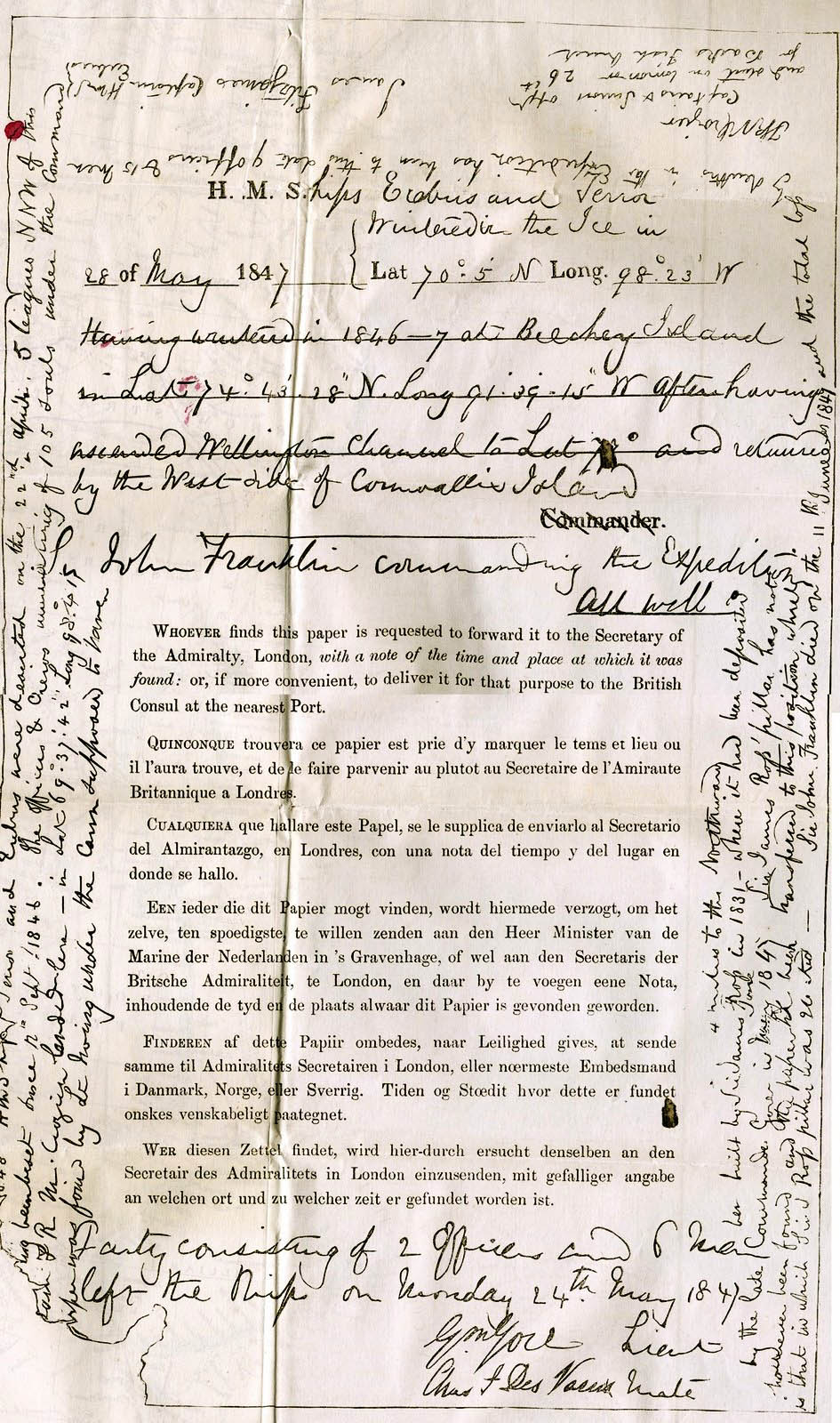

The sheet, a standard printed form used by British expeditionary crews, was the first written record found from Franklin, after more than 20 expeditions had been sent out in search of them men. Written on May 28, 1847, the note told of how Franklin’s men had overwintered about 400 miles north on Beechey Island. All were well, FitzJames wrote, but 11 months later on April 25, 1848, FitzJames had updated the form.

For 19 months, since September 12, 1846, the Terror and Erebus had been trapped in ice, the addendum added. The crews had abandoned the boats just three days prior to writing the note. One hundred and five men were alive, under the command of Terror captain Francis R.M Crozier, who had signed the note along with James Fitzjames. They planned to venture south on the twenty-sixth in search of Back’s Fish River, a river that flowed from the south into the Arctic. By this time, nine officers and 15 men had died. This included Sir John Franklin, who had perished just 13 days after the original document had been signed.

The Victory Point cairn on King William Island, as it became known, was not the first cairn found by searchers. Throughout the Arctic, teams had found and dismantled many cairns, most of which had been built by previous explorers, including the one with the note, which had been erected in 1830 by James Ross.

The Victory Point cairn on King William Island, as it became known, was not the first cairn found by searchers. Throughout the Arctic, teams had found and dismantled many cairns, most of which had been built by previous explorers, including the one with the note, which had been erected in 1830 by James Ross.

My favorite cairn is one found on Beechey Island, that was made of 600 to 700 bright red, meat tins, made by Goldner’s in London. The company had supplied Franklin with more than 20,000 tins totaling 16 tons. (One of the long debated aspects of the Franklin Expedition is whether the lead used to solder the tins had addled the men’s’ brains and lead to poor decision making.) The cairn measured eight feet high by six feet wide. Curiously, limestone pebbles filled each soup can-sized tin.

Despite more than 160 years of searching, no other written evidence has ever been found from Franklin’s Expedition. People still continue to travel to the Arctic in search though. They are still building and still dismantling cairns.