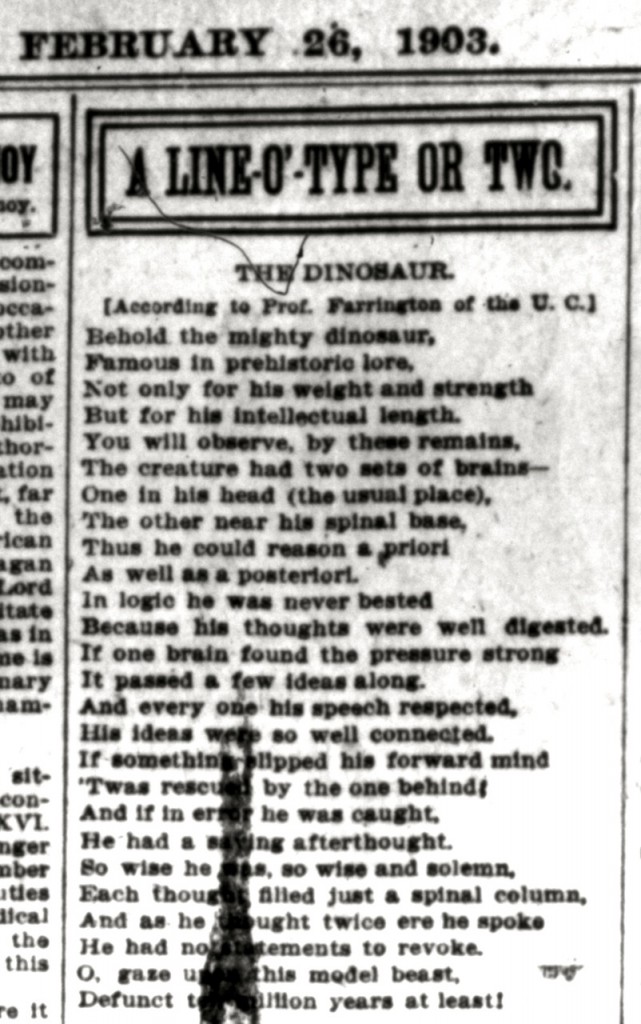

Perhaps the most famous dinosaur poem of all is one penned by Chicago Tribune columnist Bert Leston Taylor. Taylor’s poem includes this famous little ditty, which I think is quite brilliant.

The creature had two sets of brains

One in his head (the usual place)

The other in his spinal base

Thus he could reason a priori

As well as a posteriori.

Taylor’s poem is also one of the most misattributed. Nearly every time you see it, you will find it dated as 1912. Even the vaunted New York Times noted this date in a February 1998 column by C. Clairborne Ray. I am guessing that Ray, like others, was referring to a short volume of poetry by Taylor, A Line-o’-Verse or Two, which came out in 1911. But Taylor didn’t write the poem for his book. Instead, he wrote it for his A Line-O’-Type or Two column, published regularly in the Tribune. The famous words are from The Dinosaur, published in the Tribune on February 26, 1903.

The poem in the paper also includes a line that refutes another myth about Taylor’s words. They do not refer to the most infamous, supposedly two-brained dinosaur, Stegosaurus. Just below the title The Dinosaur, Taylor added “According to Prof. Farrington of the U.C.” Taylor’s reference to Farrington was in response to a photograph and short note that appeared in the Tribune the day before, on February 25.

The poem in the paper also includes a line that refutes another myth about Taylor’s words. They do not refer to the most infamous, supposedly two-brained dinosaur, Stegosaurus. Just below the title The Dinosaur, Taylor added “According to Prof. Farrington of the U.C.” Taylor’s reference to Farrington was in response to a photograph and short note that appeared in the Tribune the day before, on February 25.

Under a headline that read “Mounting skeleton of 70 foot dinosaur at Field Museum. It was so big that it required two brain to move it about,” was a photograph of about a dozen vertebrae from the museum’s Brachiosaurus. A second photo illustrates Farrington at work on a vertebrae, with an accompanying text describing his work and the dinosaur. “He [the dinosaur, not Farrington] had not only a brain in his head but another well down his back, sixty feet from the primary seat of his intelligence. The second brain station controlled the nerve power that worked the second section of his body.”

We now know, of course, that no dinosaurs had two brains. The confusion came about because of an enlarged canal in Stegosaurus‘s sacrum. To this day, the function of this body is not clear. I am guessing that a similar space in the vertebrae of the Brachiosaurus led to Farrington’s interpretation of it. We may not know its function but at least it led to a couple of wonderful lines of poetry.

We now know, of course, that no dinosaurs had two brains. The confusion came about because of an enlarged canal in Stegosaurus‘s sacrum. To this day, the function of this body is not clear. I am guessing that a similar space in the vertebrae of the Brachiosaurus led to Farrington’s interpretation of it. We may not know its function but at least it led to a couple of wonderful lines of poetry.