Modern Seattle likes to pay homage to high technology, such as apps, iPhones, and drones, but I would argue that some decidely primitive technology has had as great of impact on the city as any of the recent developments. This will be a multi-part posting. I start with the technology that drove the radical altering of Seattle’s waterfront and the Duwamish River’s tideflats and follow by exploring the tools that facilitated the city’s great regrades.

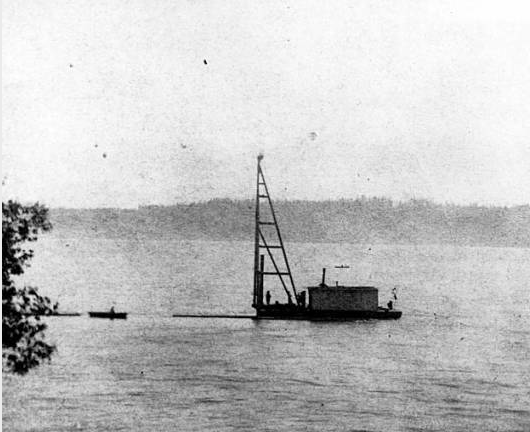

In May 1876, former Chief of Police Joe Surber floated a scow up to a dock at what is now First Avenue South and South King Street and was then the southern most point in Seattle. Sittting on the barge-like boat was a pile driver, which Surber would use to drive pilings, or wood logs, into the tideflats of the Duwamish River. Within months, he had built the first trestle, or bridge, across the tideflats; it would soon carry Seattle’s first important railroad and help transform the city.

Pile drivers, which have been around since at least the Romans, operate by dropping a heavy iron weight on the end of pile. One picture taken at the time shows Surber’s boat about equal in length to the 50-foot-tall tower that supported the iron hammer. A shack takes up the back half of the boat. Inside the shack was the steam engine that drove the hammer. With mud more than 30 feet deep on the tideflats, Surber needed piles up to 65 feet long.

Two whacks of the 3,000-pound-hammer would push the piles down through the soft mud to harder material below, with more blows—sometimes over 150—required to sink the log to a stable depth. Pile drivers used on Puget Sound in the 1890s struck 70 blows per minute. We have no record of how fast Surber worked but a report in the 1890s described pile drivers putting in from 26 to 200 piles per day.

Nor do we have any record of how many pilings were driven into shorelines around Seattle but it must number in the hundreds of thousands if not into the millions. Pile drivers built the trestles that allowed trains to cross the tideflats and to swing around downtown on what was Railroad Avenue and is now Alaskan Way; the wharves that were key to the city’s maritime trade, such as Yesler’s Wharf, which was part of Seattle’s first industry; and the thousands of piers and docks that jut out from shorelines on every body of water in the city.

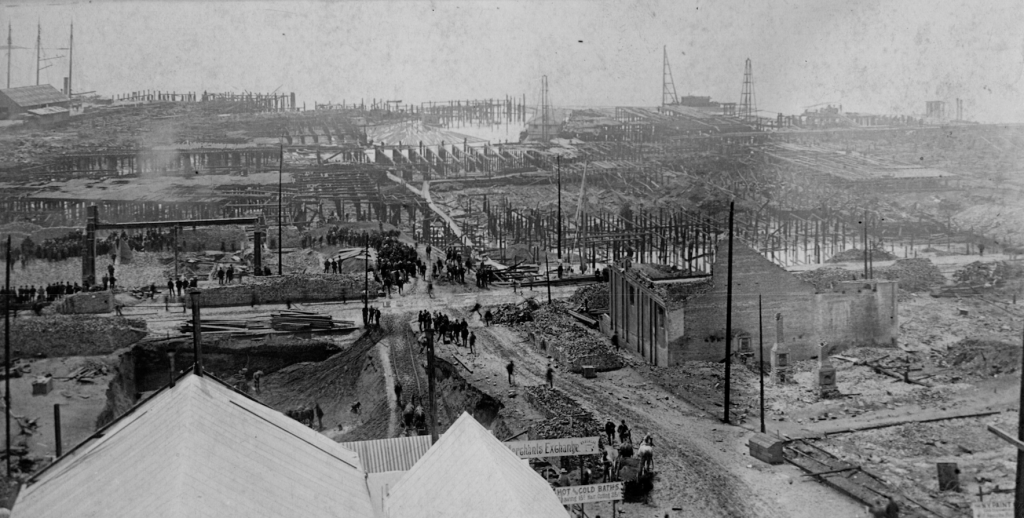

Perhaps no picture better illustrates the use of pile drivers than this one taken in the days after Seattle’s Great Fire of 1889. There are at least three in the photo, and we know that many more were in use during the rebuilding of the city. You can also see the thousands of pilings, which had helped the city grow out into the water. They were the bones essential to Seattle’s growth and every single one had been put in place by that most simple and wonderful piece of technology, the pile driver.