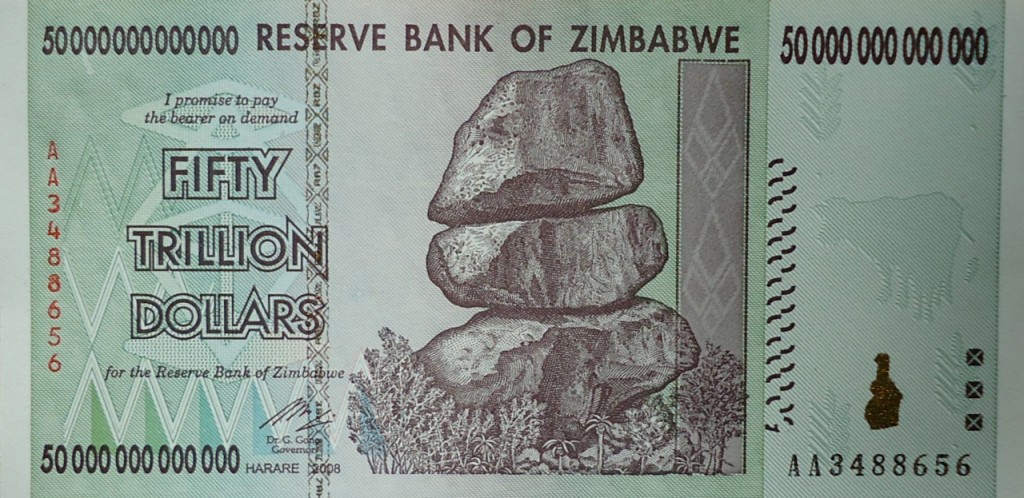

The other day a good friend gave me $50 trillion. It was a single note, the second highest ever printed. Of course, I was excited, although the money was from Zimbabwe and worth basically nothing, except what I could sell it for on eBay. The biggest thrill, beyond seeing so my zeros, was the picture on the front of the bill. It was clearly a cairn, three rocks stacked a top each other.

You can imagine the shear joy for someone just finishing a book about cairns to see one honored on currency, especially when I discovered that the cairn was used on all of the Zimbabwe currency. Soon that initial tingling of pleasure was crushed. Turns out that those three rocks are not a cairn but a stack of three, large, naturally occurring balanced rocks.

You can imagine the shear joy for someone just finishing a book about cairns to see one honored on currency, especially when I discovered that the cairn was used on all of the Zimbabwe currency. Soon that initial tingling of pleasure was crushed. Turns out that those three rocks are not a cairn but a stack of three, large, naturally occurring balanced rocks.

The rocks are found near the town of Epworth about 9 miles south of Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital and largest city. Known locally as Domboremari, or “the money rock,” they are part of a larger area called the Chiremba Balancing Rocks, which also includes the “Flying Boat Formation.” All are made of granite boulders, eroded to a perfect balance.

Apparently in the 1960s, the Rhodesian Bank’s Board of Directors wanted a well-known natural feature of the country and chose the rocks as a symbol of strength and stability. The stacked stones did appear on the Rhodesian dollar, though much less prominently than they do on the Zimbabwean currency.

Apparently in the 1960s, the Rhodesian Bank’s Board of Directors wanted a well-known natural feature of the country and chose the rocks as a symbol of strength and stability. The stacked stones did appear on the Rhodesian dollar, though much less prominently than they do on the Zimbabwean currency.

After a little sulking, a few tears, and a shot of whiskey (with Whiskey Rocks), I have gotten over my disappointment that the rocks are not a cairn. How could I complain that a country chose a rock formation a symbol? I do, however, think that a cairn would make a good emblem. After all, a cairn is a sign of aide, a guide and comfort to those who are lost, and a means of communication that has existed for thousands of years. Perhaps some day some country will see the light and use one.