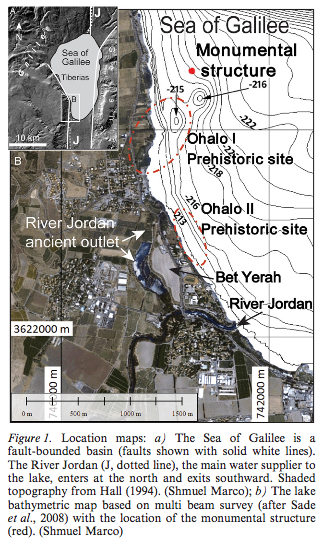

The big news in the world of cairns, which as you can imagine is truly mind-boggling in scale, scope, and power, is the discovery of the giant cairn found at the bottom of the Sea of Galilee. Archaelogists report (International Journal of Nautical Archaeology Vol 42, pg. 189-193, March 2013) that the pile of basalt cobbles and boulders has a diameter of 230 feet and rises more than 30 feet off the floor of the lake (the sea is actually a lake, in fact the lowest freshwater lake on Earth). The “Monumental Structure” was found in 2003 during a detailed mapping of the lake’s bottom morphology. With boulders up to a meter long, the rock pile provides good habitat for Tilapia fish. Other possibly similarly aged structures are found nearby in the water, though not enough research has been done to determine if they date from the same time. Archaeologists offer several interpretations for the cairn. The first, and the one I like best, is that it was built underwater to attract fish. Other similar structures described as fish nurseries occur throughout the Sea of Galilee, though they are smaller. It is also possible that it was built on land and that either rising water or a lowered ground surface, due to tectonics, lead to cairn’s present subaqueous location. There is evidence for the latter from a 23,000-old-site that apparently was buried during rapid subsidence. I like this theory, too.

Archaeologists offer several interpretations for the cairn. The first, and the one I like best, is that it was built underwater to attract fish. Other similar structures described as fish nurseries occur throughout the Sea of Galilee, though they are smaller. It is also possible that it was built on land and that either rising water or a lowered ground surface, due to tectonics, lead to cairn’s present subaqueous location. There is evidence for the latter from a 23,000-old-site that apparently was buried during rapid subsidence. I like this theory, too.

Dating the structure is also challenging. People did live in the area between the 4th and 1st centuries BCE, with active building of megalithic structures over the first 1,000 years of that era. These include stone circles, menhirs and dolmens, now found in the Jordan Valley. Archaeologists hope that further study will shed light on the cairn.

Pretty cool story.