San Francisco has long been famed for its hills. There are 43 of them, or 42, or 53, or perhaps even 49, including such well known ones as Telegraph, Nob, and Russian. As happened and still happens in many urban centers, the hills became the fashionable place to live, offering good views and clean air, high above the miasmas that lingered in the lowlands. One of the earliest of these desirable knolls was Rincon Hill, which first attracted the wealthy in the 1850s and by 1861 was described in the Daily Alta California (Feb 2) as “the most elegant part of the city.” But its enviable reputation did not last long.

As James Sederberg pointed out in his fine essay in foundSF, steep hills did not always engender themselves with San Franciscans. One of those hillophobes was John Middleton, a very influential and well-connected resident. Middleton apparently was frustrated that north-south traffic tended to avoid going over the steep edifice of Rincon by taking the low sloped Third Street, thus bypassing property he owned at the base of the hill on Second Street. One way around this problem would be to have the City cut a swath through Rincon along Second Street.

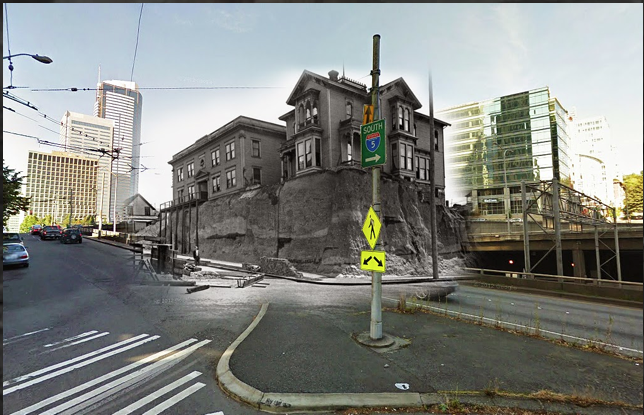

[nggallery id=36]In order to aid the city in their decision-making, Middleton ran for the state assembly in 1867, won, with a little help from his friends, and soon introduced Assembly Bill 444. It authorized a modification of the grade of Second Street for the three blocks between Bryant and Howard Streets. The deepest cut of the canyon would be in the middle, 87 feet at Harrison Street. A bridge at Harrison would connect the two sides of new canyon, with additional steps leading out of the gap.

Not everyone approved of the vivisection of Rincon, including the Alta, which reported this “astounding piece of vandalism was perpetrated …[with] no attention paid even to the most elementary rights of property.” In contrast, an editorial in Chas D. Carter’s Real Estate Circular, which was commenting on a California Supreme Court Case ruling that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors had to allow the cut, noted that the cut would lead to the filling of swamps, as well as having a “beneficial effect upon the extension of Montgomery Street.” (February 1869, v3 n4)

The cut took a year and required 500 men and 250 teams of horses. I have not been able to track down how much dirt was moved though one article in the Real Estate Circular (July 1869, v3, n9, p1) mentioned “120,000 square yards,” which I assume should be cubic yards, as that is how engineers measured these projects. Costing nearly three times more than budgeted, the total cost was about $380,000 with the Harrison Street bridge totalling $90,000.

Despite Middleton’s hopes the cut did not serve its purpose and became an unsavory place frequented by hudlums, leading one writer to note that the only way to pass through the cut was with gun in hand. It was also dangerous as the steeply cut hillsides slid during rainstorms.

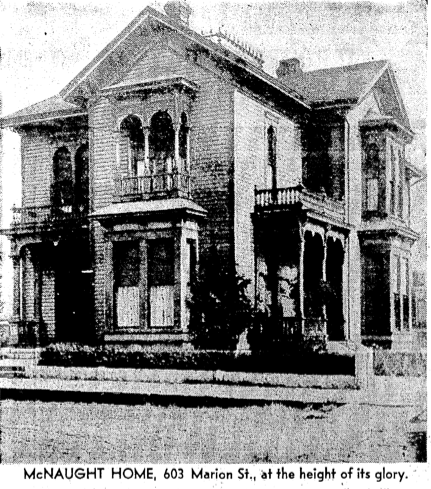

One curious aspect of the Second Street Cut, which makes it far different from regrading in Seattle, is that only the street was cut. Properties on either side of the street were not lowered at the same time. Instead, the homes were perched high over the canyon below, which might be nice in a natural setting but was certainly not good in a city. This situation led to the Real Estate Circular calling for the removal of the entire hill: “the space it occupies is required for commerce, and its removal will transform the land from private residence into business property.” (July 1869, v3, n9)

In the end, Rincon Hill became what Robert Louis Stevenson described as a “new slum, a place of precarious, sandy cliffs…solitary, ancient houses, and the butt-ends of streets.” No more hill removal was attempted after this debacle, in part because of the start of the city’s first cable car service in late 1873.

— The most detailed account of the Second Street Cut and its problems is Albert Shumate’s Rincon Hill and South Park: San Francisco’s Early Fashionable Neighborhood, which provided many details for this post.

I would also like to thank LisaRuth Elliott and Chris Carlsson of foundsf.org for their help.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.