On November 14, 1960, the Seattle Times ran a story about the “almost forgotten ‘ghost town'” under downtown Seattle. Entering through the kitchen of the B&R Restaurant at 105 1/2 Yesler Way and equipped with a flashlight, reporter John Reddin and Fire Chief William Fitzgerald descended two flights of stairs into a dim and dusty cavern. They found a series of passageways and old store fronts, as well as old wooden columns.

A week later Reddin went down under again, this time in Seattle’s original Chinatown around Washington Street and Second Avenue. Beneath the streets was a warren of “secret hallways and passages…so intricate in their windings that they were confusing even to the Chinese who entered,” according to an April 3, 1928, Times article. There supposedly was also a secret room only accessible by unlocking a latch that required putting a wood match in a concealed pinhole in a wall. Reddin never found the hole but in a subsequent story he reported on the Merz Sheet Metal Works at 208 1/2 Jackson. (I like the sort of Harry Potteresqueness that so many of the underground spots have that 1/2 added to the address.) Curiously, the shop was 14 feet below the modern street. Outside the subterranean shop one could still see the original sidewalk.

Most people know about these underground passages through Bill Speidel’s Underground tour, but what they may not know is that the tour barely scratches the subsurface of these passages. In addition, the city monitors all of these spaces, or what they call “areaways.” The areaways developed after Seattle’s Great Fire of June 6, 1889, when the city council replatted the downtown area. In particular, they called for the expansion of Second and Third by taking 12 feet from each side, which would make these thoroughfares 90 feet wide. Front and Commercial would also grow from 66 feet wide to 84 feet. And a new street would appear on the maps, the 120-foot-wide, Railroad Avenue, located west of Front and Commercial streets.

Just as critical to enlarging the channels for business to flow was establishing a consistent grade for the new streets, which translated to raising them. Most of the Pioneer Square streets would be raised above the city’s datum point by an average of five feet per block. The map below shows how high above the datum.

Most business owners supported the city council’s call for better streets, but they wanted to build immediately and the city could not match the pace. The issue was not widening, which was relatively simple since everyone was starting from scratch and a foundation could be built where necessary, but widening required major infrastructure change. The city had to erect brick or stone retaining walls, on the old streets, find material to fill in between the walls, transport the material to the site, fill in the street, and finally pave over, usually with wood, the surface of the new, higher street.

Not willing to wait, business owners started to build. Using stone and brick—the city had banned wood—they located their first floors at the level of the old streets. Since the city had yet to raise the streets, the sidewalks were also at this old level, which made it easy to enter the new business establishments.

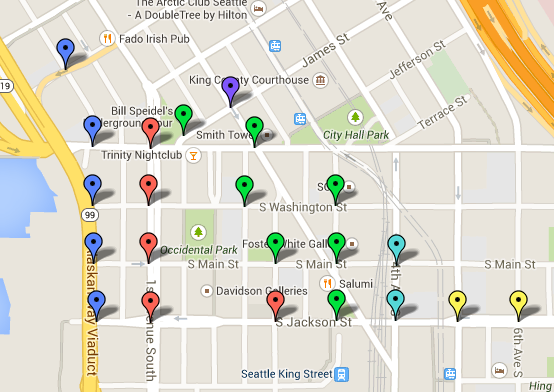

As you can see from the map above (large files so may take a bit to load), the areaways extend throughout Pioneer Square. Below is the most up-to-date map of them I could find, where you can see that not all of them are in good shape. Intriguingly, at one point the City briefly considered using them for stormwater control. The idea was that water could flow into the open spaces. A study determined it was impractical because each original property owner was responsible for building up their facade and passage, which lead to a myriad of strategies and qualities.

[nggallery id=35]

Another way to trace the location of the areaways is to look for sidewalks with glass blocks. Flat on top and prismatic below, the glass let light into the subterranean canyons. Initially developed in the 1840s as deck lights for ships, vault lights were popular in cities, including New York, Chicago, Victoria, B.C., and Boston, from the late 1800s through the 1930s, when electric light prevailed. All of the prisms were originally clear and have since turned purple due to magnesium dioxide, which changes color under long term exposure to ultraviolet light. The reason you don’t see more in Seattle is that individual building owners are responsible for the vault lights in front of their building and it’s cheaper to cover them over than to upkeep them. There are still about 9,000 vault lights in the city.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.