I was recently contacted by Todd Ellis, a photographer based in southern Utah, who sent me this unusual, and I think subtly striking photo of a cairn from his neck of the words.

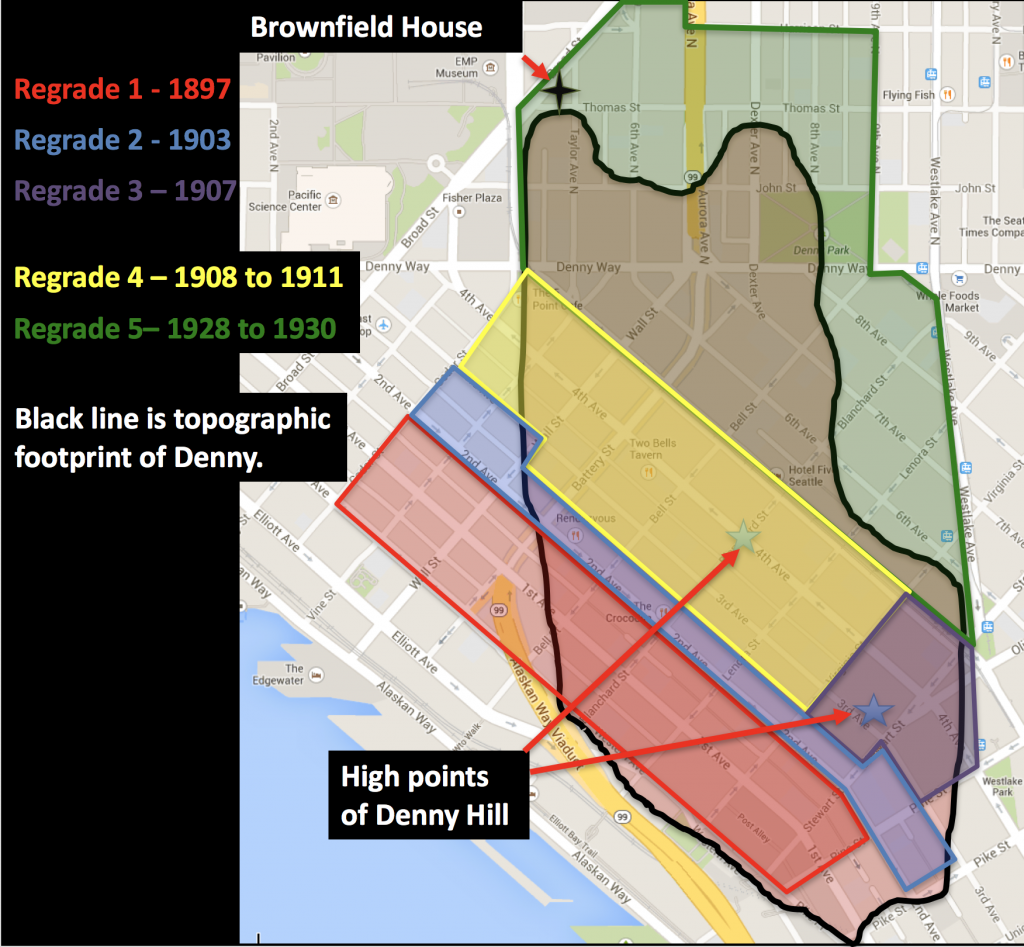

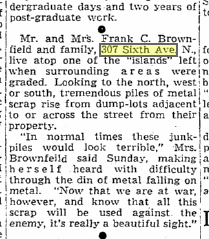

An obituary appeared in the Seattle Times today that I suspect few will notice, but the man who died marks the end of an era. His name was Curt Brownfield. I know of him because he lived in the last house left standing on a mound during the Denny regrades. It stood on a small rise at 307 Sixth Avenue North, at what is the present location of the Seattle City Light Broad Street Substation.

The Brownfield’s have deep roots in Seattle. In 1867, Curtis’s great-grandfather Christian and his wife homesteaded what would become the University District. Five years later, Christian and his son Curtis were hired to pull coal cars across the land connecting Lake Union and Lake Washington. Once the cars were across, they went onto the steamer Clara, which Curtis piloted down the lake to meet Seattle’s first railroad.

In 1906, Curtis’s son Frank, Curt’s father, moved to the house on Sixth Ave. Frank eventually became a marine engineer for Associated Oil Company. He lived there with his wife Mary and their six children. Curt was the fourth child, born in 1929, during the middle of the final regrade of Denny Hill. He lived at the house until 1942, twelve years after the regrade had been completed. (In October 2016, I was alerted to the fact that I had misplaced the Brownfield house on the original map that I had used. I have fixed that map to show that the house was between Thomas and Harrison and not Thomas and John, where I had originally placed it.)

During the research for my book, Too High and Too Steep, I was fortunate to speak to Curt about his experience growing up in the house. His first line to me in reference to the regrade was “that was a dumb idea.” (He also told me “Yeah we owned the U-District.”)

“My parents were not very cooperative. They didn’t see why they should just pay anything extra,” said Curt. “They just wanted to live there. They weren’t going to benefit from the regrade.” So they decided not to go along with the city’s plans, which worked out well for Curt and his friends. There were no other houses around and the area became a sort of dumping ground that the youngsters would scavenge for fun items such as artillery and an Enfield rifle.

To get up to the house, which was about 20 feet above the surrounding terrain, they had a wide ramp cut into the hill. It led to a flight of stairs up to the level ground of the house. In front, they could climb a steep metal staircase, which Curt’s father said came from a ship they were scrapping out. They usually used the back entrance as it was closer to the trolley tracks. To get coal up to the house, the coal man had to carry it up, Santa Claus-style, in a big bag.

“People all around us were sold on the idea that once this area was flat, the property was going to become very valuable and developers were going to come in,” said Curt. “It was the wrong presumption. It never happened. The depression took over and business went downhill. Most people all lost everything. We didn’t lose everything because we didn’t go along with the regrades. It wasn’t a bad decision. It was a good decision not to have our house moved.”

By the early 1940s, Curt’s older brother had made enough money to buy a new house for his parents and the family moved to the top of Queen Anne hill. “My brother and sister were a bit embarrassed by the house,” said Curt.

A ship worker then moved into the house. He didn’t stay long though as on August 11, 1945, real estate operator James L. Napier, who had purchased the property, filed a permit for destroying the house. Later, the city built the power substation that still stands on the property.

Denny Hill was finally gone and now too is Curt Brownfield. My condolences to his family and thanks to his son for facilitating my interview. It was an honor to talk to Curt.

(Some of this text comes from Too High and Too Steep.)