Karen Daubert, Executive Director of Washington Trails Association, recently sent me information about an initiative about cairns in the northeast. The goal is to protect cairns on mountains, as well as to protect the environment where the cairns are built. According to longtime Appalachian Mountain Club volunteer Pete Lane, “Cairns in our area are being damaged and as alpine stewards, we need lots of help to get the word out about leaving them as they are.” As Lane and others involved in the working group note, cairns have long been an essential element of safe hiking in northeast but in recent years these wonderful little piles of rocks have not fared well. The initiative is organized by Leave No Trace.

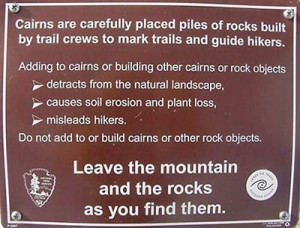

People not only are destroying cairns but also building too many of them, which can lead people astray and damage the environment, when cairns builders pry up rocks in the fragile alpine ecosystems for cairns. This situation has particularly been bad in national parks and along the Appalachian trail, where people regularly damage cairns despite the best efforts of rangers and volunteers.

The working group has published a set of guidelines for minimizing impact on cairns. Here they are. (From the web site.)

1. Do not build unauthorized cairns. When visitors create unauthorized routes or cairns they often greatly expand trampling impacts and misdirect visitors from established routes to more fragile or dangerous areas. This is especially important in the winter when trails are hidden by snow. Thus, visitor-created or “bootleg” cairns can be very misleading to hikers and should not be built.

2. Do not tamper with cairns. Authorized cairns are designed and built for specific purposes. Tampering with or altering cairns minimizes their route marking effectiveness. Leave all cairns as they are found.

3. Do not add stones to existing cairns. Cairns are designed to be free draining. Adding stones to cairns chinks the crevices, allowing snow to accumulate. Snow turns to ice, and the subsequent freeze-thaw cycle can reduce the cairn to a rock pile.

4. Do not move rocks. Extracting and moving rocks make mountain soils more prone to erosion in an environment where new soil creation requires thousands of years. It also disturbs adjacent fragile alpine vegetation.

5. Stay on trails. Protect fragile mountain vegetation by following cairns or paint blazes in order to stay on designated trails.

All good advice, which is applicable to anywhere you find cairns, whether in the northeast, the Sierras, or the American southwest. With hiking season on us, this another good lesson in how to lessen our impact on the ecosystems we love to explore.