I freely admit that I have probably spent too much time looking down at my feet while exploring Seattle. I have probably spent too much time looking up, too. But whether I gaze skyward or sidewalk-ward, I am often rewarded. For instance, I think I am one of the few people to notice several duck tracks in concrete and to connect them to the duck in terra cotta just a few blocks away. I guess I just have an affinity for making brilliant deducktions. (I know, groan, but I couldn’t pass it up.)

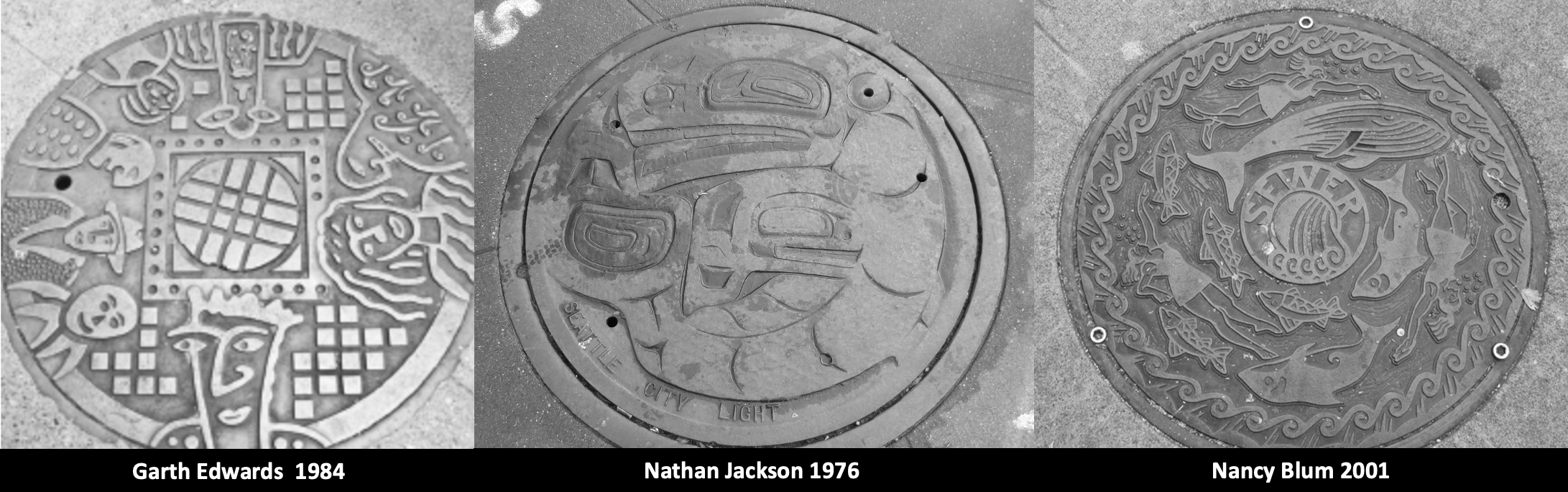

Far better known than the tracks are the hatch covers throughout downtown. (Since personhole cover is a disgusting term and manhole a problematic term, hatch cover or utility cover are the preferred names.) The idea for Seattle’s hatch cover art began in 1975 after Seattle Arts Commissioner Jacquetta Blanchett traveled to Florence and saw the city’s hatch art. Working with Department of Community Development director, Paul Schell, Blanchett donated enough money to fund 13 covers, with six more paid for by other donors. Each cost $200 and weighed 230 pounds. There are now numerous designs adorning our streets.

My favorite hatch cover, of course, is a map, first put in place in April 1977, on the north edge of Occidental Park. It is still there.

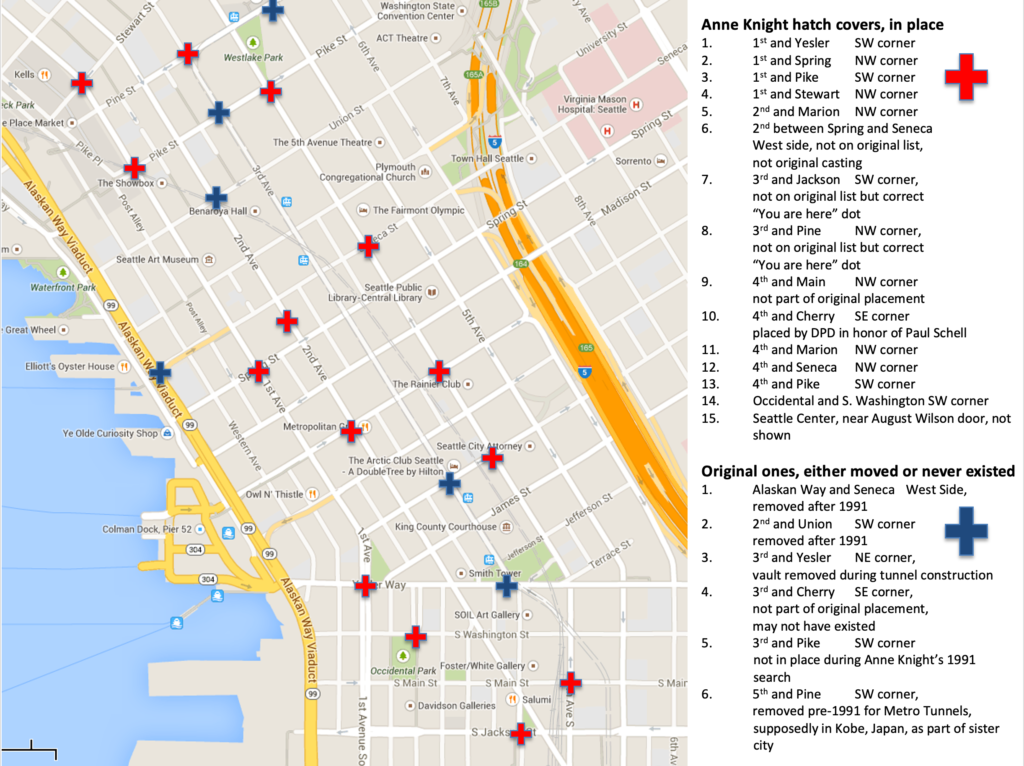

Anne Knight designed the map. A map was natural because Seattle had such a “graphically interesting street pattern,” she said. Anne thought that the map covers would make an excellent teaching guide, as well as a guide to the city. If you look at the covers (except one), you will see there is no compass. A City of Light employee had told Anne that one thing he didn’t want was a compass on the map. Otherwise, the crews would have to orient the cover correctly each time. So there is no compass, though there is a map, which one would hope wouldn’t be too challenging for the City of Light crews to orient. Apparently it is. Despite Anne including a small welded bead on the outer ring of each cover to facilitate easy alignment, nearly all of the covers are misaligned at present.

Anne told me that a police officer had heard about the project and called her to say he was concerned that pedestrians would be stopping in the middle of the street to look at the maps. She told him not to worry as she had only chosen spots on corners.

Each of the maps includes city landmarks, such as the post office, the Seattle Public Library, King Street Station, and Denny Park. You can figure out which one is which by looking at the key on the map’s outer edge. All of the landmarks still remain except for the Kingdome. “At the time it had just been built and I thought naively that it looked like it was a structure that would be there forever,” Anne said.

Curiously, the manhole cover on Second Avenue between Spring and Seneca has a unique, post 1975 landmark on it. That landmark is the Seattle Art Museum. In order to fit that landmark on the key, Harborview Hospital was dropped. The map is also the only one not on a corner. (Anne does not know the exact origin of that cover; a special one was made for the Seattle Art Museum but it was removed when the Hammering Man fell and damaged it.)

As you can see from the accompanying annotated map, not all of the original covers exist. I could locate 14, plus the later one added on Second Avenue. One is now in Kobe. (This one had been moved to an alley and a City of Light employee had removed it and happened to have it in his truck when he attended a sister city meeting and suggested sending the cover to Kobe.) Several others have been moved and/or removed with their whereabouts unknown. Another that was on the original list apparently was never in that location and there is one at the Seattle Center at the northwest corner of the fountain lawn at what would be the SE corner of Republican St (August Wilson Way) and Second Ave N.

These manhole maps are one of the delights of Seattle. So next time you are out walking around downtown, take a look down at your feet. You might be amazed at what you find. And, watch out for that terra cotta duck. Who knows where she’ll land next.

I also know of one other map hatchcover. It’s at Waterway 15, at 4th Avenue NE and NE Northlake Way, on Lake Union.

This posting is part of my Seattle Street Smart newsletter. If you are interested in subscribing, here’s the link.