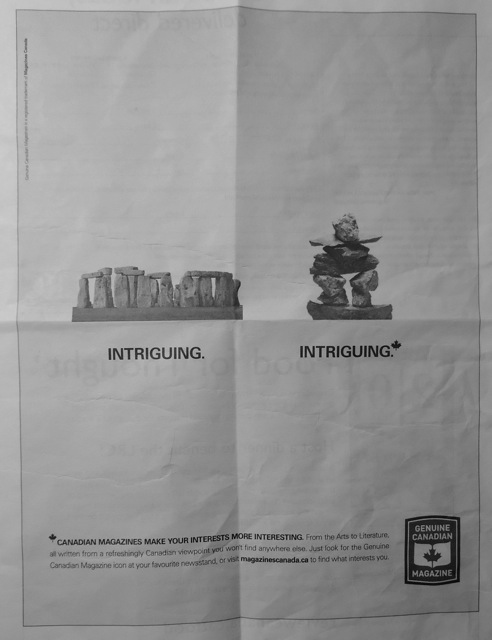

I have to hand it to the Canadians. They have great advertising. I recently came across this nifty advertisement on the back of the Literary Review of Canada.

Where else but in Canada would you see a squat pile of rocks labeled as Intriguing? Of course, the main reason for the rise of the rocks is the Vancouver Olympics of 2010. Its symbol was known as Ilanaaq, or “friend” in the Inuit language. More generally, the rock pile is a type of cairn called an inuksuk, which translates to “that which acts in the capacity of a human.” The people of the north have been building inuksuit for thousands of years but not until the Olympics did marketers firmly appropriate them as a new symbol of Canada.

Where else but in Canada would you see a squat pile of rocks labeled as Intriguing? Of course, the main reason for the rise of the rocks is the Vancouver Olympics of 2010. Its symbol was known as Ilanaaq, or “friend” in the Inuit language. More generally, the rock pile is a type of cairn called an inuksuk, which translates to “that which acts in the capacity of a human.” The people of the north have been building inuksuit for thousands of years but not until the Olympics did marketers firmly appropriate them as a new symbol of Canada.

This ad must be one of the few around that features only rocks: Stonehenge and an inuksuk. It clearly reveals that marketers are beginning to realize the power of rocks as a tool for attracting people. I mean who doesn’t get excited by seeing rocks carefully placed in an attractive setting. Someday soon, I suspect that such geology-themed ads will become the norm for all marketing worldwide.

This ad must be one of the few around that features only rocks: Stonehenge and an inuksuk. It clearly reveals that marketers are beginning to realize the power of rocks as a tool for attracting people. I mean who doesn’t get excited by seeing rocks carefully placed in an attractive setting. Someday soon, I suspect that such geology-themed ads will become the norm for all marketing worldwide.

But back to this ad. I also like the scales used in it. It looks as if the inuksuit could have built Stonehenge. (Just a quick aside to note the famous mini-Stonehenge used by the great band Spinal Tap.) Perhaps the Genuine Canadian Magazine marketers have inadvertently solved one of the great conundrums of English history. Who built Stonehenge? Was it an inuksuk? Certainly just as likely of answer as some that have been tossed out. Good job Canadians.

But back to this ad. I also like the scales used in it. It looks as if the inuksuit could have built Stonehenge. (Just a quick aside to note the famous mini-Stonehenge used by the great band Spinal Tap.) Perhaps the Genuine Canadian Magazine marketers have inadvertently solved one of the great conundrums of English history. Who built Stonehenge? Was it an inuksuk? Certainly just as likely of answer as some that have been tossed out. Good job Canadians.