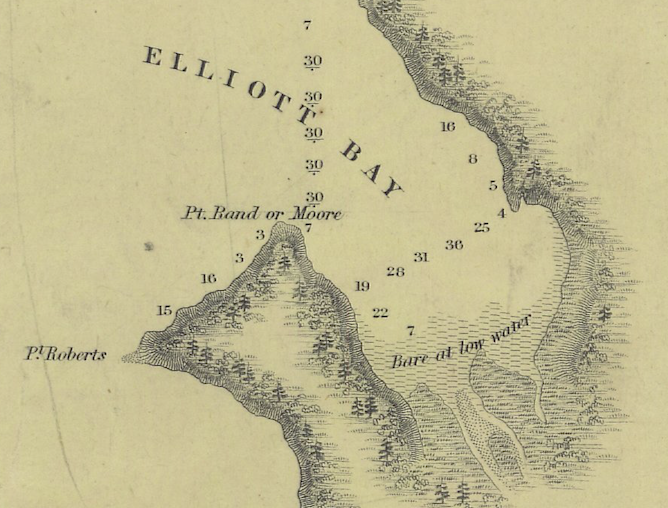

Over the past few weeks as I have been wandering the Seattle streets for my new book of urban walks, I have noticed a feature that I had previously noted but not thought too much about. It’s the handful of places in town where the name of the street is embedded in the sidewalk.

I have not been able to determine when any of these names went in or who did them and why but here’s a little background. In 1902, the city adopted Resolution No. 387, which declared “that all concrete sidewalks laid in the City of Seattle shall have the names of the streets countersunk in plain letters at the street intersections…” Two months later an article in the Seattle Times noted that R.H. Thomson, chair of the Board of Public Works, wanted “red cement [to] be used to fill the lettering so that a very pretty effect can evidently be had.” I have not been able to any red street names so suspect that Mr. Thomson’s preference was never practiced.

Apparently street naming tiles were somewhat common around the turn of the twentieth century. The preferred style was to use are known as encaustic tiles, “made by the American Encaustic Tiling Company of Zanesville, Oho, in a style called ‘Alhambra’. The ‘Alhambra’ style consisted of a pearly white background and precise, royal blue Roman letters, each with a dark grey double outline.” This style can be found in Victoria, BC.

1. The most common in Seattle are blue and white tiles, which look a bit like the encaustic ones. There are several on Madison Street, including one with a spelling that looks as if it was done by a wee child. Here are the locations of those tiles.

–Madison & East Thomas (between 26th & 27th)

–Madison & East Thomas (between 26th & 27th)

–E. Lee St. (at E. Madison St.) [near 37th]

–28th Ave. N (Now Ave. E. – Madison Valley)

–29th Ave. N. (at E. Madison St.)

–E. Madison St. (at 32nd Ave. E.)

–32nd Ave. N. (at E. Madison St.)

–33rd Ave. N. (at E. Madison St.)

–E. Madison St. (at 37th Ave. E.)

In addition, the corner of 12th Ave. NE and NE 52nd St., in the University District, bears tiles of this style. I don’t know of any others in the UDistrict.

But if you really want to see blue and white tiles, go to Ballard, which has the most by far. Here is a map of them.

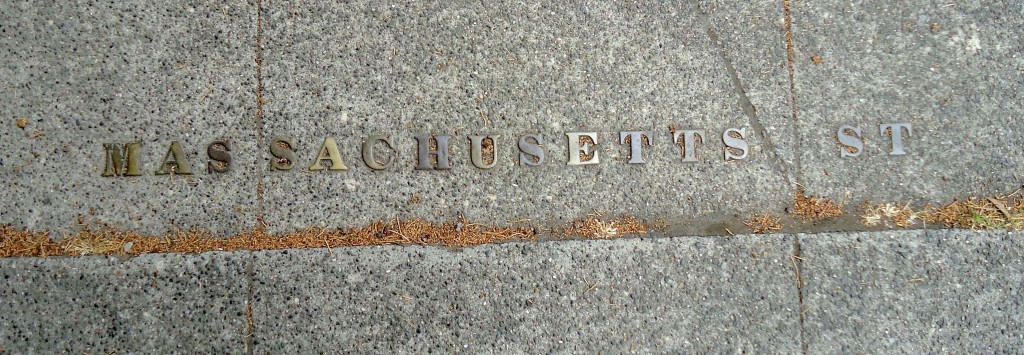

2. Downtown Seattle also has severaal streets with names embedded in the sidewalk. Instead of tile, the names are large bronze letters. Most of the ones I have seen are along Third Avenue between Seneca and Pine streets.

3. Beacon Hill – Several bronze names are embedded in sidewalks along South Massachusetts Street between 12th Avenue South and 14th Avenue South.

3. Beacon Hill – Several bronze names are embedded in sidewalks along South Massachusetts Street between 12th Avenue South and 14th Avenue South.

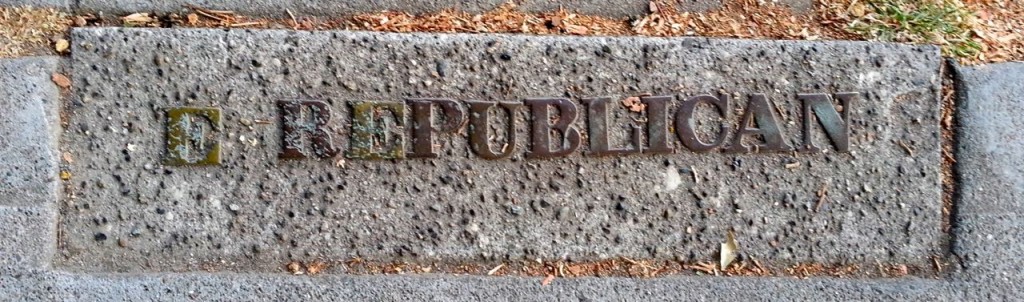

4. Capitol Hill – Found one corner with small bronze names at 11th Avenue East and East Republican Street.

4. Capitol Hill – Found one corner with small bronze names at 11th Avenue East and East Republican Street.

5. Others, that I learned about since my first post:

5. Others, that I learned about since my first post:

– SW corner First Avenue South and South King Street, font is sans serif, unlike other bronze ones (from Rob Ketcherside)

– SW corner of Fifth and Union. Large bronze letters ala Third and Union.

– The letters O and K in front of 2209 First Avenue. This used to be the Hotel Scargo. No idea when the letters went in or what they stand for.

-17th Avenue E. and Marion Street, small lettering as in other parts of Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill.

-W. Garfield St. and Fourth Avenue W. in Queen Anne, small lettering as in other parts of Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill.

-Sixth Avenue W and W. Blaine St. in Queen Anne, small lettering as in other parts of Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill.

-Seventh Avenue W and W. Blaine St. in Queen Anne, small lettering as in other parts of Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill.

-NW corner of Terry Avenue and Spruce St, small lettering as in other parts of Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill.

If you do know of any others please let me know.