On July 29, 1895, thousands of Seattleites came out for what one paper crowned “the greatest enterprise yet inaugurated in this city.” They stood on a barge, watched from docks, and looked on from boats. (Fortunately, wrote one reporter, that nasty “old Sol” was hidden behind the clouds and no one would get too hot.) All were in the protean landscape of the Duwamish River’s tideflats, which for half of the day was underwater and for the other half was an expanse of mud. They had come to see an unusual boat.

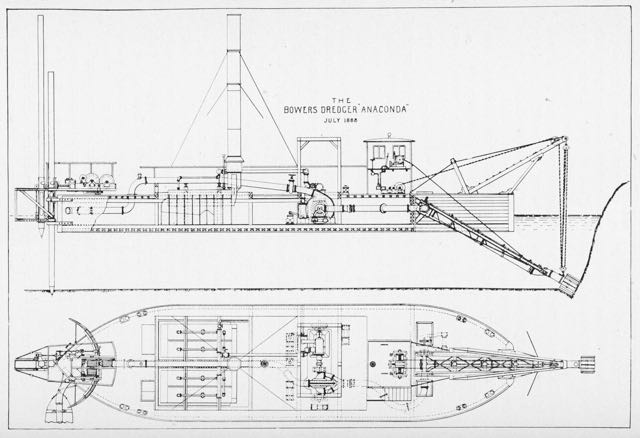

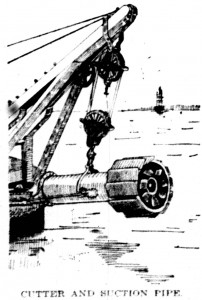

The Anaconda was 110 feet long and 32 feet wide with a spewing smoke stack and strange stern, which was attached to a long pole anchored into the tidal mud. The bow was also odd with a hoist that held a movable cutting head. The two part structure consisted of a seven-blade spinning cutter inside a 13-blade rotating cutter. Extending out of the hollow cutter was a suction pipe connected to a huge centrifugal pump. Built to suck up muck, the Anaconda could discharge 10,000 cubic yards of material every 24 hours.

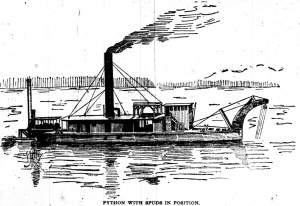

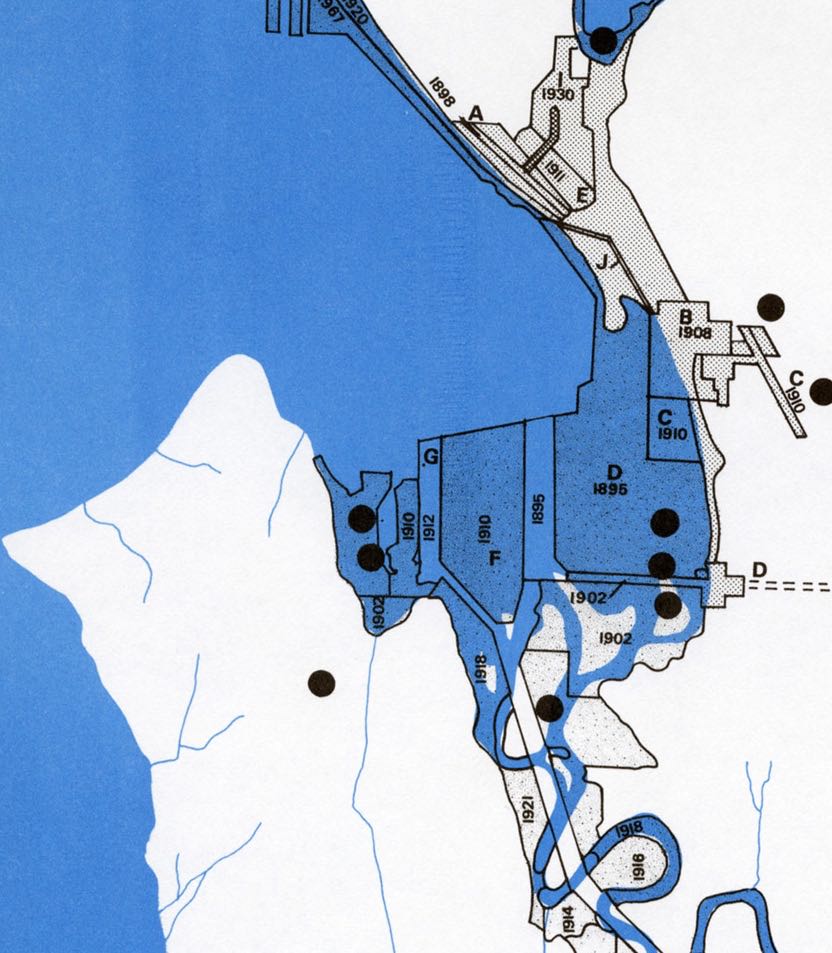

Eugene Semple, who had organized the event, owned the Anaconda. His plan was to use it and a sister dredger, the Python, to pump sediment from one part of the tideflats to another, in the process making new land for the city of Seattle. The main source of sediment would could from the Anaconda and Python excavating what are now the East and West Waterways on either side of Harbor Island. That sediment and material from the Jackson Street and Dearborn Street regrades, as well as from Semple’s failed attempt at a South Canal, would eventually lead to making around 2200 acres of new land.

On that great day, Semple stood in the upper deck of the Anaconda’s engine room with his daughter Zoe. A reporter noted that Miss Semple made “a very pretty picture as she stood clad in a pure white costume…with a waist made of white dimity … and [a] skirt of white ducking.” (If any reader can educate me on what this means, I would appreciate it.) At 11:29 A.M., Miss Semple stepped up onto a wooden block, reached toward a small lever with her hand, and pushed it.

The Anaconda began to shudder as cogs turned and set in motion the blades of the cutting tool sunk into the mud 25 feet below the surface of Elliott Bay. Mud and water began shooting through a stationary pipe suspended above the tideflats. The 2,700-foot-long pipe curved northeast on triangle-shaped trestles to an area that is now just west of Safeco Field. At the time it was adjacent to the southern most wharves and piers in Seattle, where most of the crowd watched the event.

The pipe expelled the mud onto tideflats recently protected by a brush bulkhead. The structure consisted of two or more pile rows ten feet apart with six feet between piles. At the base directly on tidal mud was a mattress of young firs laid between the rows and built to one foot above low tide. Resting atop the mattress were 24-foot-long bundles of brushes, called fascines. Sand had also been pumped over the fascines to strengthen the support wall; the excess water escaped through the branches. With every three feet rise in elevation, a horizontal tree would be laid perpendicular to the bulkhead with its bare trunk over the fascine and its branched end extending into the area destined for fill. Additional strength came from anchoring the mattress and fascine to the tree trunks. More fascines and more tie-backs would be added until the fill reached two feet above high tide line.

By June 1897, the Anaconda and Python had excavated three thousand feet of the East Waterway to a depth of thirty-five feet below low water, which created 75 acres of made land. Seven years later, after various legal and financial setbacks, the total had risen to more than 333 acres. By 1917, about 92 percent of the tideflats had been filled.

The last area of filling was west of Harbor Island, along the edge of West Seattle. It had remained somewhat wild through the 1940s, with a stream cutting across a sandy lowland but after World War II, industries, including a plant for creosoting wood pilings, a ship building facility, and later a banana warehouse, began to make the area more suitable for their needs.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

2 thoughts on “Filling the Flats”