Welsh naturalist Edward Lhuyd was the first to describe fossils from Stonesfield. In his 1699 Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographica, he illustrated two teeth, one of which he described as that of a fish. Lhuyd believed that fossils formed from “exhalations which are raised out of the sea” carrying fish-spawn that got caught in chinks in the ground and became fish fossils. He added that such fossils “have so much excited our admiration, and indeed baffled our reasoning.”

But the Stonesfield didn’t become truly famous until the 1800s and the discoveries and descriptions of William Buckland. One of my all-time favorite geologists, Buckland was an ordained priest in the Church of England; notorious for eating practically everything; one of earliest professional geology instructors, at Oxford University; a fellow of the Royal Society; and the first to recognize the importance of coprolites (he coined the term). His eccentricities earned him a famous description by Charles Darwin, who wrote of Buckland: “though very good-humoured and good-natured [he] seemed to me a vulgar and almost coarse man. He was incited more by a craving for notoriety, which sometimes made him act like a buffoon, than by a love of science.” Oh Charles, don’t be so stuffy.

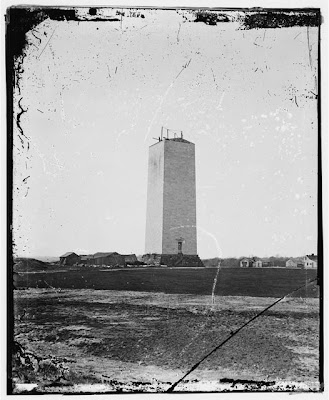

William Buckland

We do not know exactly when Buckland obtained his famous fossils because he failed to jot down this fact. Those who have studied the issue have put the date as no later than 1818, due to an 1824 article by Georges Cuvier. No matter when he found them, Buckland made a formal description of a lower jaw, teeth, and a huge thigh bone on February 10, 1824, at a presentation to the Geological Society in London.

Buckland ascribed his fossils to a carnivorous reptile at least forty feet long and weighing as much as an elephant. In honor of its larger-than-life size, at least larger than any known land animal, he named it Megalosaurus, the Great Lizard. Twelve years later, Richard Owen would include Megalosaurus, along with Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus, in his new order of animals, Dinosauria.

The Megalosaurus tooth and jaw of Buckland

Curiously, the so-called Stonesfield slate isn’t slate, which makes sense considering the source rock is so fossiliferous. It is, in fact, limestone, deposited in a shallow marine environment. The bones most likely washed into the water followed by rapid burial by sand transported offshore during storm events. Other fossils found in the quarries include fish, reptiles, mammals, ammonites, bivalves, gastropods, insects, and 13 species of terrestrial plants.

Stonesfield slate from www.gowildgardening.co.uk/buildings.htm

Quarrymen split the Stonesfield slate in a rather nifty manner. Instead of using hammer and chisel, the men relied on cold weather. They would pull the limestone out of the ground (20 to 70 feet deep) in a rough block called a “pendle” and let it sit in a field and absorb water. To ensure moisture retention, the quarrymen would pile dirt atop the blocks and/or douse the stone in water. Over several cold winters, water would penetrate the bedding planes and split the stone into usable pieces. In some cases the split piece would be round and be dubbed a potlid. Builders highly prized the thin slabs of Stonesfield slate, using them in colleges at Oxford.

Recently, English researchers have taken a new look at Megalosaurus and its family Megalosauridae (Palaeontology, v. 51, no. 2, 419-424). They have concluded that the family should be discontinued because of a lack of clear evidence allying the genera that have previously been listed as Megalosauridae. The only reptile that is clearly “megalosaurid” is the one found by Buckland. Perhaps Mr. Darwin should have been more generous in his observations.