U.S. Assay Office NYC, formerly New Branch of the Bank of U.S. (found on this web site)

One of the earliest uses for Tuckahoe was in the New York branch of the Bank of the United States. Designed by Martin E. Thompson, the building became the US Assay Office in 1853 and in the early 1900s was the oldest federal structure in NYC. Such fame, however, didn’t save it from destruction in 1915. Curiously, the Tuckahoe façade was re-erected in Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Tuckahoe also achieved great fame in 1846 when Alexander T. Stewart, who would become one of New York’s wealthiest men, opened the city’s first large department store. Designed by the wonderfully named firm of Trench and Snook, the massive store was faced in Tuckahoe marble and quickly earned the moniker the “Marble Palace.”

Stewart also built a huge mansion with the marble, which unfortunately did not benefit the owner of the Tuckahoe quarry. According to the February 25, 1899 American Architect and Building News: “Mr. Stewart made a contract with the owner of the quarry, fixing a heavy penalty, amounting, practically, to the forfeiture of the quarry itself, for delay in delivery, beyond a specified time, of the marble. The delivery was delayed beyond the time, and Mr. Stewart determined to enforce the forfeiture. According to the story which was current in our younger days, the owner of the quarry went to Mr. Stewart to plead for mercy, but found him obdurate, and, overcome by grief and excitement, fell dead before him.”

Now to the corruption. Our story begins in 1861 with the construction of the county courthouse in New York City. The original budget was $250,000. As happens in many good civic projects, the builders decided to work with local stone, in this case the Tuckahoe marble. But this was the era of William “Boss” Tweed, a man who took corruption, bribery, and payouts to new heights. As he gathered more and more control over New York, Tweed made the County Courthouse into a money mill for himself and his cronies. For example, carpenter George S. Miller received $360,751 for one month of work; “Prince of Plasterers” Andrew Garvey got $2,870,464.06 for his efforts; and one company owned by Tweed charged $170,727 for chairs, all 40 of them.

In 1864, Tweed and pals purchased a marble quarry in Sheffield, Massachusetts for $3,080. Initially, the country ordered $1,200 worth of stone, which by 1867 had somehow morphed to costing $120,000. Over the years of construction, the county shelled out at least $420,000 for new, uncut marble for the courthouse. The courthouse was eventually completed in 1881, at a total cost of $12 million.

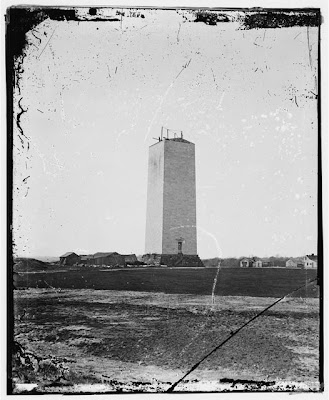

Over a century later, a decision was made to restore the courthouse. The initial study found that about 8 to 10 percent of the stone needed to be replaced. Most of the stone for restoration came from Georgia but workers also located 125 marble blocks in the Sheffield quarries. They had been slated for use in the Washington Monument (only four rows of Sheffield are in the obelisk, sandwiched between Texas and Cockeysville marbles) but after Tweed was convicted of wrong doing, no one wanted the stone. Now they are back in New York, apparently at true market cost.