The Cliff in Iowa

When the trailer for the film, which featured the Corvette shot, first appeared last year, many fans in the Trek universe were sent into a tizzy about the cliff. They knew that the driver of the car, a young James Kirk, will grow up in Iowa, but did not know of any such cliffs in Kirk’s home state. One wrote that because there aren’t any big cliffs like that in Iowa, the shot completely ruined the movie. I agree. If you are going to spend all of that money on a fictional, fantasy movie where people can use a transporter for travel, at least get the geology right. Others, however, contended that Kirk might have been on a road trip or that perhaps in the future someone would dig such a hole in Iowa.

The road trip idea fits in best with the filming. Consider that the scene is supposed to take place in Iowa was mostly shot outside of Bakersfield, California, and that the quarry is in Vermont.

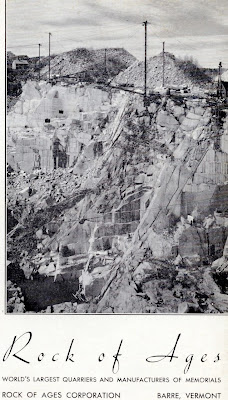

The quarry hole that Mr. Kirk’s nice red Corvette shoots into is the E. L. Smith Quarry, started near Barre, Vermont, by Emery L. Smith, a Civil War veteran. After the war he returned to Barre, married, and started to acquire properties, eventually owing over 70 acres. Out of their quarries came the stone for the State House in Montpelier. The Rock of Ages corporation purchased the quarry in 1941 and still own it. The pit is now roughly 600 feet deep. The quarry produces a light gray granite, which formed during the Acadian Orogeny, sometime around 370 million years ago.

Rock of Ages Quarry, photo used courtesy of Peggy Perazzo, http://quarriesandbeyond.org/

According to press reports recently blasted out of Vermont, the crew came and shot the quarry without any actors in May 2008. They rented a helicopter and spent a day shooting aerial and still shots but wouldn’t say why or for what film. Using computer graphics apparently they then added the quarry face to the scenes shot in California. I guess with computers you don’t need a transporter.