The other day my mom asked me a very basic question and one that I had never considered. How exactly did they lower Lake Washington during construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks? Completed in 1916 and officially opened in 1917, this was one of the great engineering feats of Seattle history.

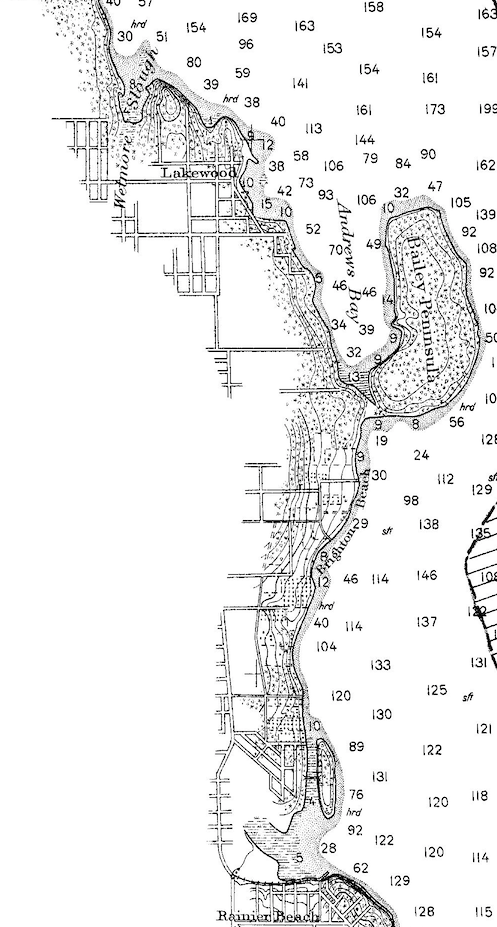

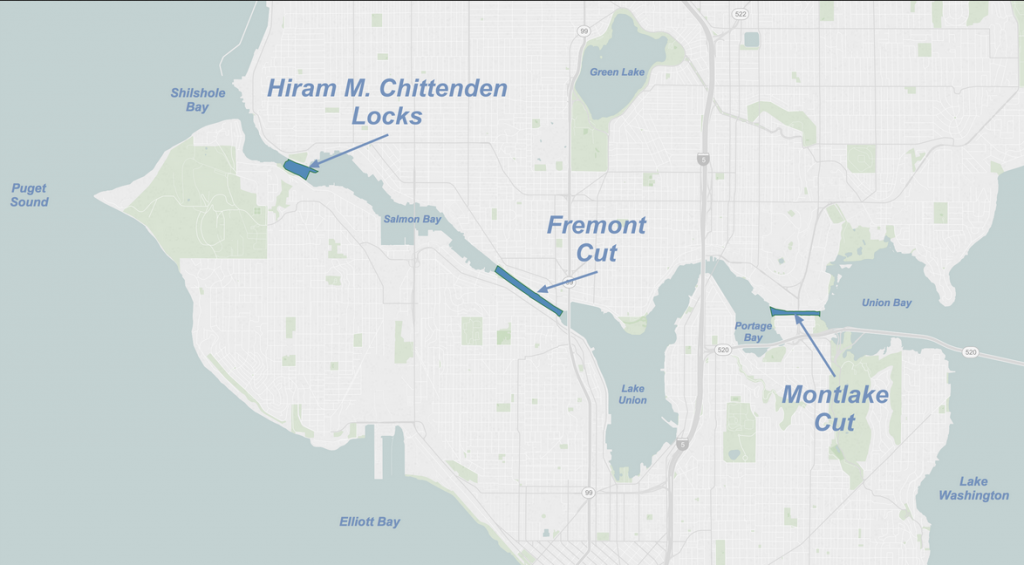

In order to keep the canal system (it consisted of two canals, or cuts, one at Montlake and one at Fremont) at the same water level, Lake Washington (LW) had to lowered down to the level of Lake Union (LU). (See map above to see how Salmon Bay connected via the Fremont canal to LU and LU connected to LW via the Montlake canal.) This necessitated about a nine foot lowering, as LW was 29 feet above sea level and LU at 20 feet. The LW number is not exactly accurate because the lake level fluctuated by as much as eight feet during the year; it was highest in winter. In addition, Salmon Bay, which historically had been a tidal inlet—filling at high tide and mostly draining out low tide—had to be raised up to the level of LU.

In regard to my mom’s question, I had long known that it “took” three months to lower LW but didn’t know the details on how they did it. Here’s a timeline of how they lowered the lake and raised the bay.

July 12, 1916 – Locks closed in order to flood Salmon Bay and raise it to the level of Fremont canal and Lake Union. “Within thirty days the greatest fresh water harbor on the Pacific seaboard will be open to ocean-going ships entering Puget Sound,” reported the Seattle Times. This was a typical response to the opening of a fresh water port in Salmon Bay.

July 30, 1916 – Steamer F.G. Reeve first boat to pass through the locks, which opened the long desired passage from Salmon Bay through the Fremont canal to Lake Union, now all at the same water level. Reeve used the smaller of the two locks.

August 3, 1916 – Snag steamer Swinomish, under the command of Capt. F. A. Siegal, was the first boat to pass through the larger lock, “amid handclapping, cheers and the blowing of whistles,” wrote Thomas Francis Hunt in the Seattle Times. More than 2,500 people attended the opening. Next boat through was the Orcas. Both vessels did a quick spin in Salmon Bay before returning back to the locks.

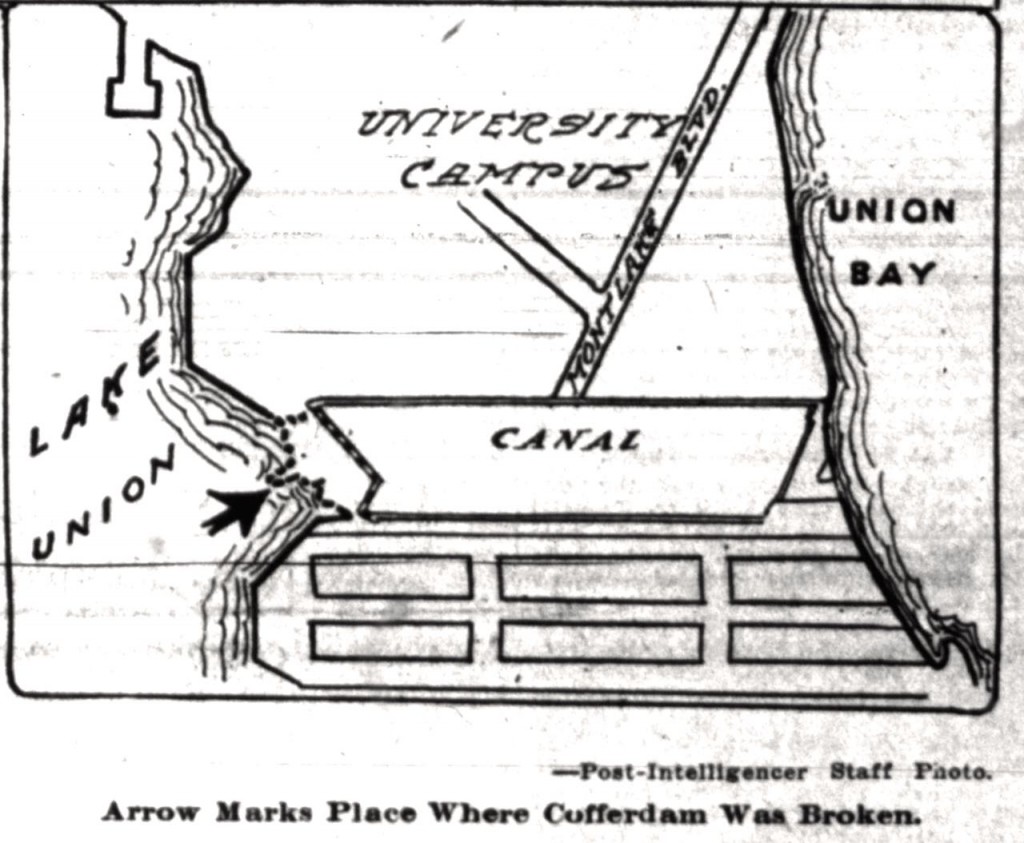

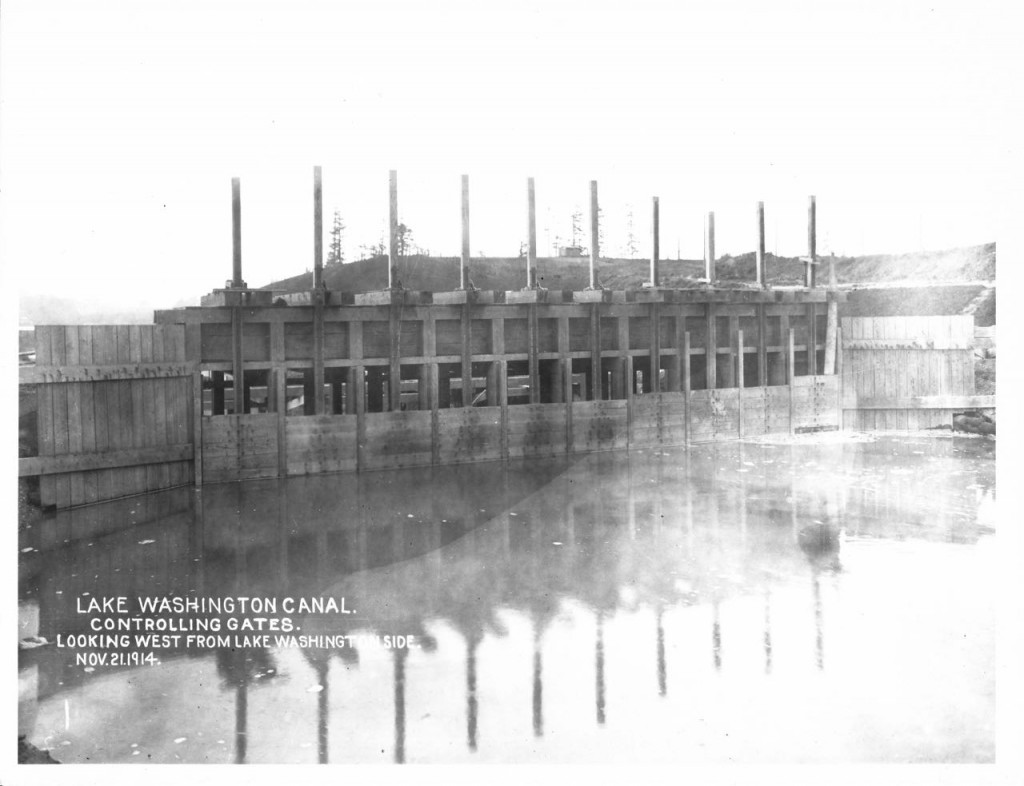

August 25, 1916 – At 2 p.m., laborers used shovels to cut an opening into the cofferdam (temporary dam built to keep water out of the way) on the east side of Portage Bay. The plan was for the water to flow out of Lake Union and fill the Montlake canal. At the east end of the canal, or the very west side of Union Bay, were sluice gates, which would control the water flowing out of Lake Washington, still nine feet higher than Lake Union. An unknown skiff piloted by an anonymous man and two bare-headed boys was the first to run the canal.

“In exactly fifty six minutes the cut (Montlake canal) was filled to the level of Lake Union, and before the hour was up the current had ended and the eddies had ceased to foam. Logs torn from the cofferdam by the charging waters and hundreds of timbers and boards which covered the bottom of the cut floated to the surface…When the men with their shovels had broken the narrow neck of land, they sprang aside just in time to escape the inflow of water…In ten minutes the crowds on the cofferdam fled to escape being plunged into a raging torrent on the sides of the bank, which caved in in huge sections,” reported the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

August 28, 1916 – Sluice gates in Lake Washington opened to allow water level in the lake to drop. Level was to be reduced about one and half feet in the first week with it dropping four feet by the end of September. Lowering Lake Washington down to the level of Lake Union did not occur until October.

By late October 1916 – Lake Washington and Lake Union and Salmon Bay are at the same level and boats can travel from Puget Sound to Lake Washington.

July 4, 1917 – Official opening of the locks and ship canal.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.