So she’s not moving again. A few days ago Bertha’s barge got tippy, then on Tuesday, the ground near her started to give way and a massive sink hole appeared. Today, we have Governor Inslee putting out a cease and desist order, immediately stopping any further work by Bertha. The old gal cannot get a break.

I’d like to put this project in a bit of historical perspective. I am not apologizing for the slowdown but would like to point out that we have had a few projects that took more time.

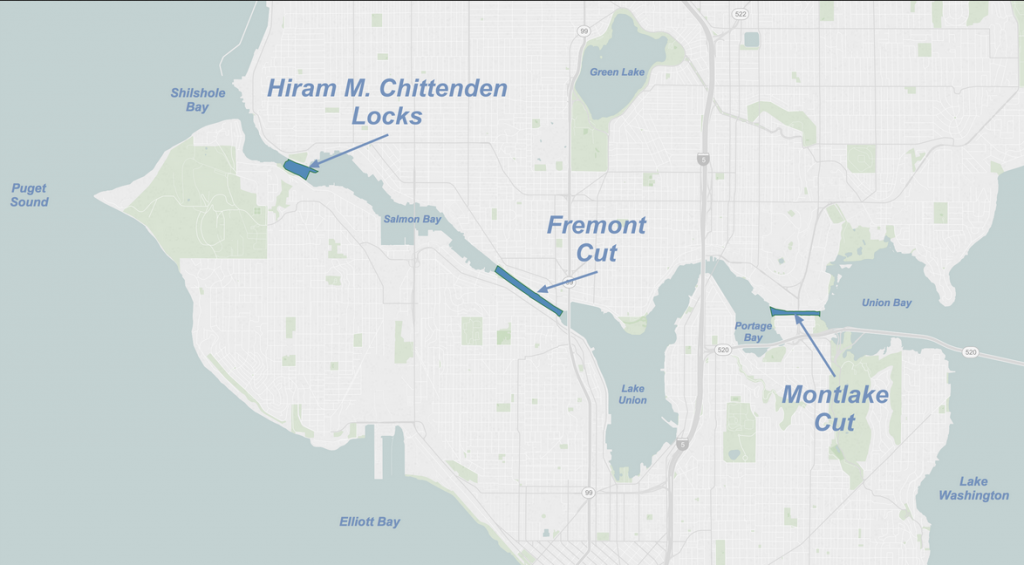

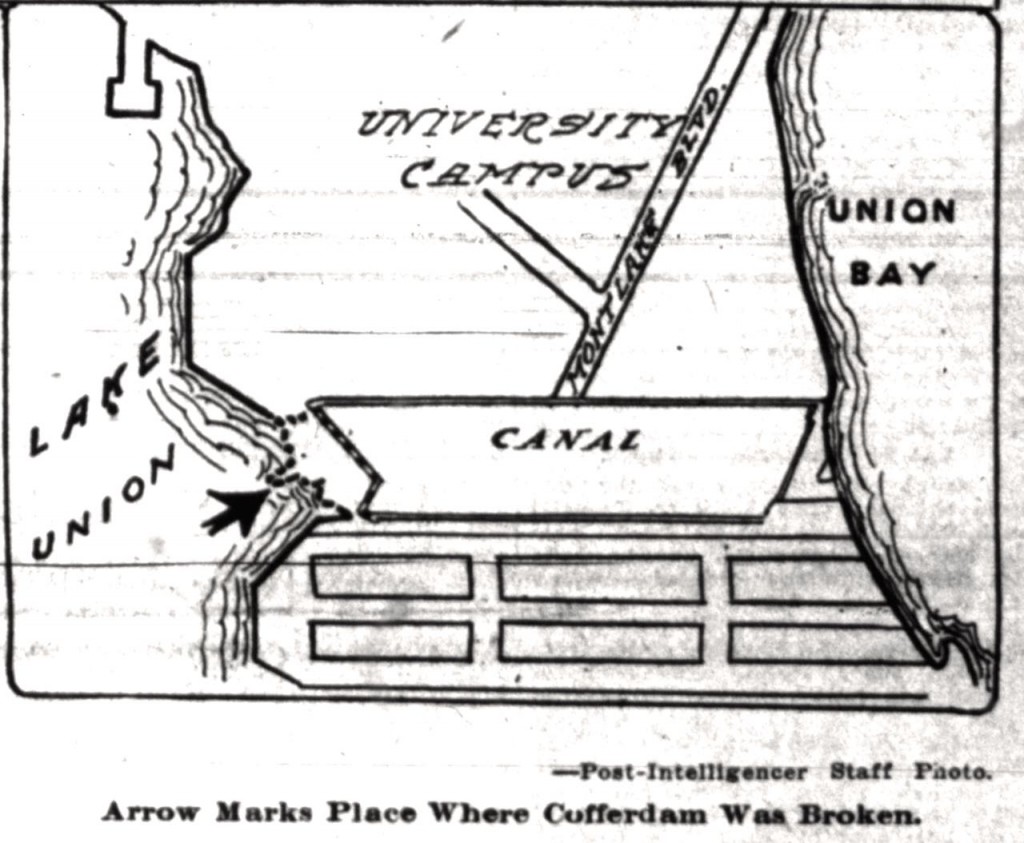

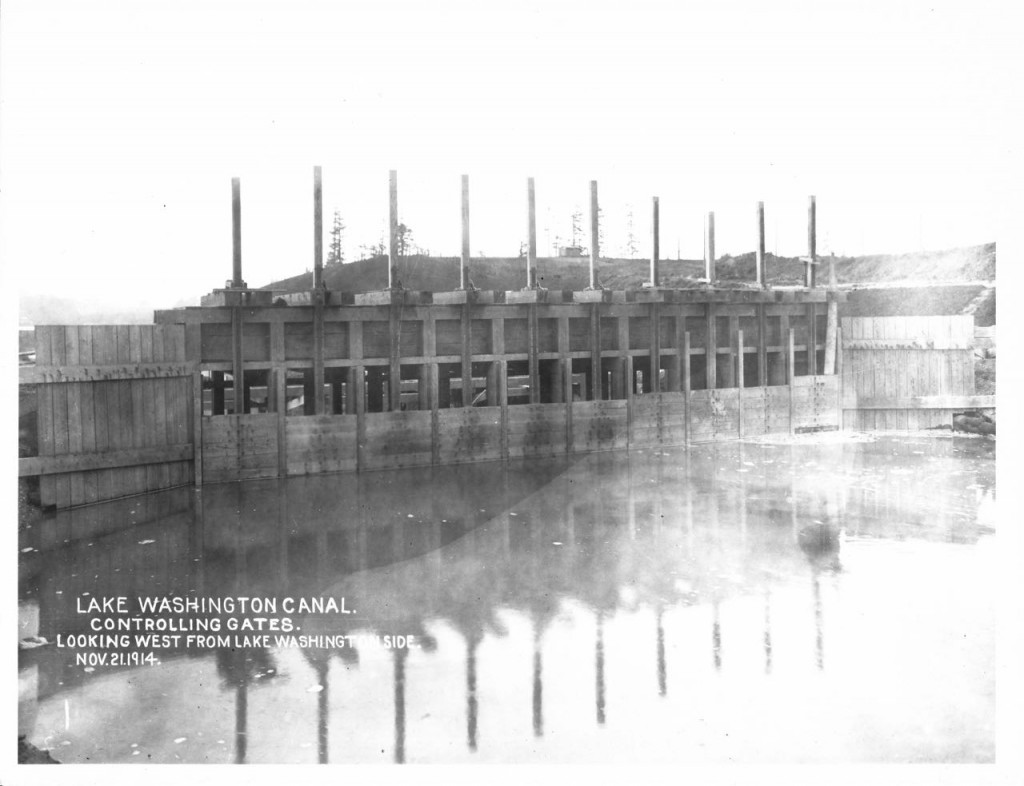

Lake Washington Ship Canal and Locks – 63 years from conception to completion. Thomas Mercer was the first to propose a linkage between Lake Washington and Puget Sound via Lake Union, way back on July 4, 1854. The canal and locks officially opened on July 4, 1917. During the six decades it took to complete the project, there were federal reports, engineering reports, and naval reports. Attempts to dig the canal were made by lone individuals, speculators, Chinese work crews, and private corporations. And finally six different routes, including one through Beacon Hill, were proposed. Not until federal funding came through was the canal completed and it still took five years to complete the work.

Filling in the Duwamish River tideflats – At least 23 years. Seattle’s citizens had been dumping material in Elliott Bay since the upstart town’s earliest days but formal filling in of the tideflats didn’t start until July 29, 1895. In what was called the “greatest enterprise yet inaugurated in this city,” a dredge began to suck sediment out of one side of the tideflats and deposit it behind a barrier 2,000 feet away. By 1917, more than 90 percent of the tideflats had been filled, creating the monumentally unstable land of SODO and Harbor Island. Work had been stopped by lawsuits, the principal dredge company running out of money, and the occasional mechanical breakdown.

Denny Regrade – 33 years from first to last removal of sediment. It took five regrades to get rid of the great mound of Denny at the north end of downtown. The first was in 1897, followed by work in 1903, 1906, 1908-1911, and 1928-1930. There were workers who were electrocuted, who were attacked by children, who lost their arms, and who were crushed by landslides. A child taking a shortcut through the project died when dynamite being heated over an open flame exploded. Citizens sued the city and corporations. Corporations sued back. And, they even had problem with barges, which sank and ran into docks, shutting down the regrade. But on the plus side, they did find fossils from a mammoth, and they did complete the project.

So next time Bertha experiences a few delays, remember, she has a long way to go to break any record for most enduring Seattle project.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.