Recently, Kelly Brenner asked me to participate in the PNW Nature Blogger Scavenger Hunt. The goal will be to answer a nature question on each of a variety of PNW nature blogs, just one question per blog. The hunt has been scheduled to begin on Monday at 8 a.m. and will run through Friday, 3-20-15.

Recently, Kelly Brenner asked me to participate in the PNW Nature Blogger Scavenger Hunt. The goal will be to answer a nature question on each of a variety of PNW nature blogs, just one question per blog. The hunt has been scheduled to begin on Monday at 8 a.m. and will run through Friday, 3-20-15.

Here is my addition to the fun. It is fairly long.

I like to think that I am knowledgeable about Seattle’s early history. I generally do well on those local history quizzes that newspapers publish when there is a slow news week and one of my earliest memories is of interviewing a descendent of a pioneer family for a story I wrote in third grade.

Despite having a head full of cocktail party-worthy facts about Seattle, I have been wrong for many years in the image I held of what Seattle looked like when the first settlers arrived. My botanical ignorance centered on big trees; I thought that a nearly unbroken forest of Douglas fir covered the hilly terrain from the shores of Puget Sound up to the Cascades. I pictured a forest “whose dark verdurous hue diffused a solitary gloom – favorable to meditations,” as naturalist Archibald Menzies wrote in 1792. It was an image fashioned partially by the women of the Denny party, Seattle’s founding families, who wept when they first arrived at Alki Point and discovered a dripping forest of giant trees.

When I began to investigate Seattle’s past I discovered my lack of knowledge. As I looked through old scientific journals and early survey reports, read modern ecological studies of the region, and talked to botanists, historians, and ecologists, I discovered far more complexity than I expected, particularly in regard to bogs, or what has been called a “history book with a flexible cover.” (May Theilgaard Watts, Reading the Landscape: An Adventure in Ecology, 1957)

Bog formation requires three factors, one of which relates to our damp climate and the other two to our glacial history. A surplus of water is the first need, a requirement met by our maritime-influenced high precipitation and mild temperatures. Second and third are infertility and poor drainage. As many local gardeners know, when the glaciers retreated 14,000 years ago, they deposited low nutrient soils but they also left behind shallow depressions, where water could stagnate. Bogs are generally restricted to the north, with the majority of North American ones in Canada and Alaska, and the majority of Washington state ones in the Puget lowlands. Although Seattle meets these conditions rather well, bogs were never common within city limits.

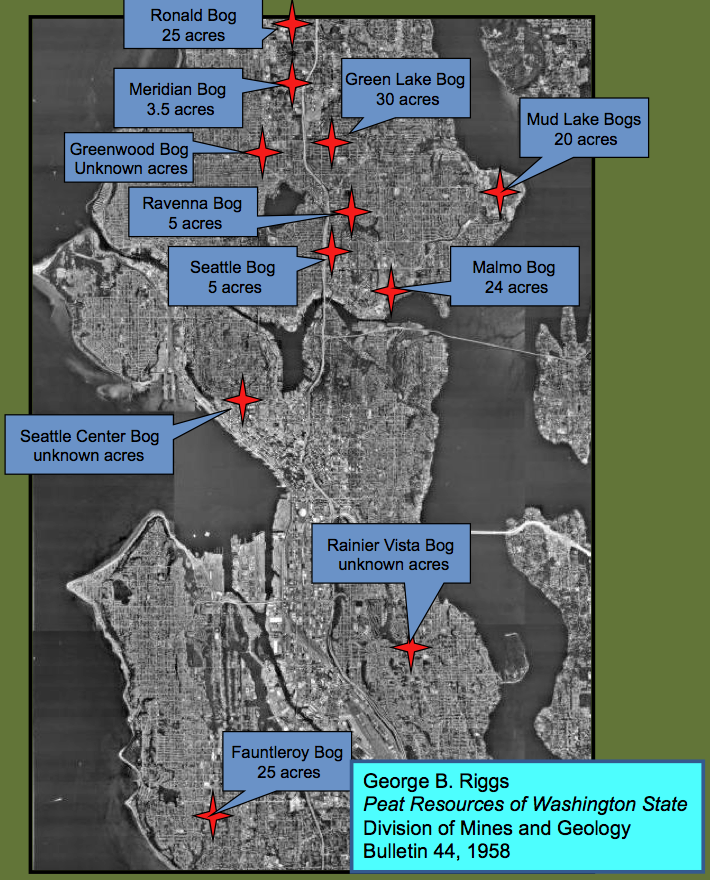

In searching through the scientific literature, I located descriptions of only a handful of in-city bogs, all of which no longer exist. As so often happens with wetlands, they were paved over for more useful purposes. For example, two have been covered by shopping centers, a 24-acre peat area under University Village and a cranberry bog now paved over by Northgate Mall. Others are known to have existed but simply passed too quickly from bog to home for anyone to write about.

Ironically, some modern residents have discovered a boggy clue, in ways that they probably wish they did not have to. In the summer of 2002, people living near 87th and Greenwood, in north Seattle, noticed cracks appearing in their walls. They also watched as two sinkholes formed, foundations sunk, and sidewalks buckled. Coincidentally, a new Safeway was the third major building project at that intersection in the past two years. It was also the third major construction site to have to pump millions of gallons of water from the site and the third to discover peat beds under the property.

I have not been able to determine when Seattle’s bogs disappeared but a landmark 1958 report on peat resources in Washington does not list a single bog within the city. The report, however, does mention clues that residents who lived in Seattle in the first half of the 1900s could have found. If they had visited a local garden store, like Malmo Nurseries, they could have purchased bags of peat moss, which had been mined from the former bogs. In peat mining, sphagnum moss is dug by hand, set out to dry, and then shredded and packaged. Some locals, in particular Japanese farmers, also made use of bogs, by draining them, and planting them with lettuce, cabbage, and other truck garden vegetables. Now, even these clues are gone with paving having replaced peat, Canadian sphagnum having replaced local sphagnum, and agribusiness having replaced small farms.

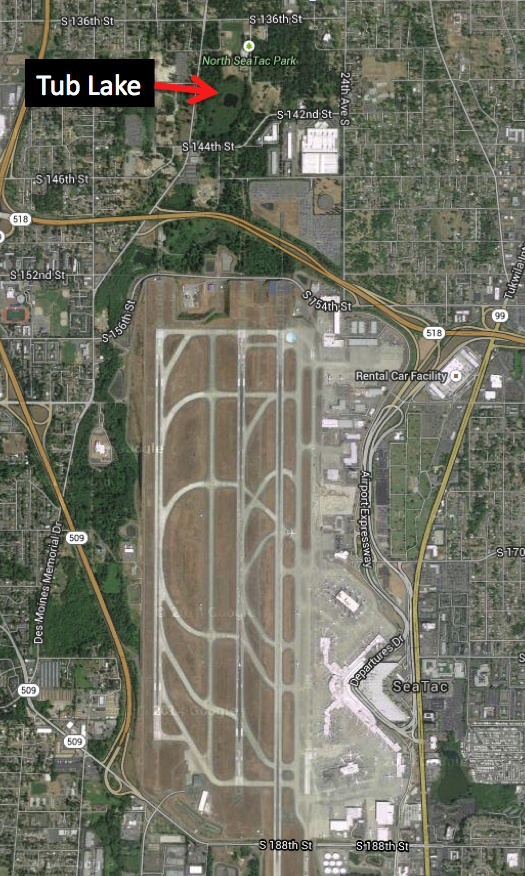

But we are in luck, one true bog remains, just outside city limits. It is a small lake just north of SeaTac Airport. To reach the water, known as Tub or Bug Lake, I parked on Des Moines Memorial Drive, walked east down a narrow path through blackberries, scrambled though a hole cut in a chain link fence, and continued to a narrow ditch, spanned by a circumspect looking 2 by 10. Such moats are a typical feature of bogs. Vegetation growing along the moat included hardhack (Spiraea douglasii) and western hemlock, which are stunted and may be as old as 300 years, even though they are only four inches in diameter.

The plank was surprisingly sturdy, as opposed to the “land” on the other side, which felt like walking on trampoline. I was not actually standing on terra firma but on a thick accumulation of muck, brown, spongy matter, technically defined as sphagnum moss decomposed past recognition. As I walked atop the muck, water squeezed out from under my feet and accumulated in low spots in the path. After 25 yards or so, I moved out of the muck onto moss peat, also brown and spongy, but less decomposed than muck. I was now standing on a floating mat of sphagnum and peat and could make the nearby western hemlocks sway by jumping up and down and sending a wave through the mat. It only took about ten more minutes of jumping and swaying, jumping and swaying, for the novelty to fade.

The high acidity and permanent water made this environment no place for Seattle’s usual botanical suspects. Instead, I found bog laurel and Labrador tea, classic bog plants. In spring, the laurels produce spectacular pink blossoms. Labrador tea has smaller white flowers and both have dark green leaves that curl under at the edge. Searching under the shrubby tea and laurel, I also located ground hugging cranberries, which along with one of Washington state’s few carnivorous plants, sundews, only grow in bogs. I was past the sundew season but I know of others who have found them at this bog.

In another twenty feet, I was at Tub Lake. I didn’t dare jump up and down at this point, as I feared my floating mat would break off. Sedges, rushes, and cattails grew at the water’s edge and pond lilies floated in the water. If I had enough time, on the order of hundreds of years, I could stand at this point and watch as the sphagnum mat grew out into the water and the lake became a forested meadow, growing on top of the peat moss. Certainly a better fate then becoming a shopping mall.

I originally wrote most of this for my book, The Seattle Street-Smart Naturalist: Field Notes from the City. I have not been back to Tub Lake in over a decade so cannot tell you if it is still accessible. If you do go, please be careful and respect any signs you see.