Brian’s story focuses on an archaeological dig run by Stephen Brighton of the University of Maryland, College Park. Brighton has been studying the Irish immigrants who left Ballykilchine and traveled to a small settlement a bit north of Baltimore. By around 1860, Texas—so named for a volunteer regiment, the Texas Greens, established for the Mexican-American War—had 600 people. Brighton says that the Irish came for the calcite, in the form of marble for quarrying and limestone for burning.

Little remains from the heyday of the Irish in Texas. Little is also available in the history books, which is what led Brighton to investigate. “It’s a huge gap…in understanding the Irish diaspora,” he says. What he has been able to piece together is unusual. The Irish stayed in Texas for generations, in contrast to the more typical dispersal out from the original center.

Brighton and his students began their dig in July 2009. Their major find was a outhouse, as well as coins, a lice comb, and numerous pieces of glass. He and his students will continue to study their artifacts in order to better understand this unusual group of immigrants.

Brian reports that the value of Texas stone was reported as early as 1811. Quarrying began in 1834 with 13 quarries opened up by 1847. Geologists call the stone the “Cockeysville Marble,” for a nearby town. First deposited 500 million years ago as limestone, the white stone turned to marble around 240 million years ago during the assembly of Pangaea.

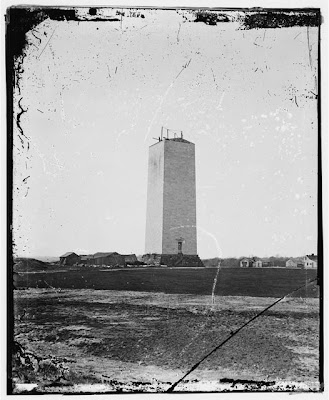

Library of Congress description “Washington Monument as it stood for 25 year,” photographed by Mathew Brady circa 1860

The color and location of the marble led it to be the first building stone of any large amount sent by rail to Washington D.C. In 1845, builders began to use the marble from Texas in the Washington Monument. They had put up 152 feet by 1854, when money ran out. Work began again in 1879, with marble from Lee, Massachusetts, but it was too costly, so the rest of the monument was finished with marble from Cockeysville, which accounts for the color change in the big edifice.

Texas marble also went into the “porticoes of the House and Senate wings of the U.S. Capitol building and the towers of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City,” writes Brian. He has written a nifty story about stone once again revealing the connection between people, geology, and history.