Another day, another problem with Bertha. This time it has to do with cracks and settling and groundwater and planning and fixing and … It’s amazing how many problems that Bertha has had. I want to focus in on the newest map released by WSDOT. Shaped perhaps ironically like another embattled landscape—Israel—the WSDOT shows the ground surface settling around the Bertha access pit.

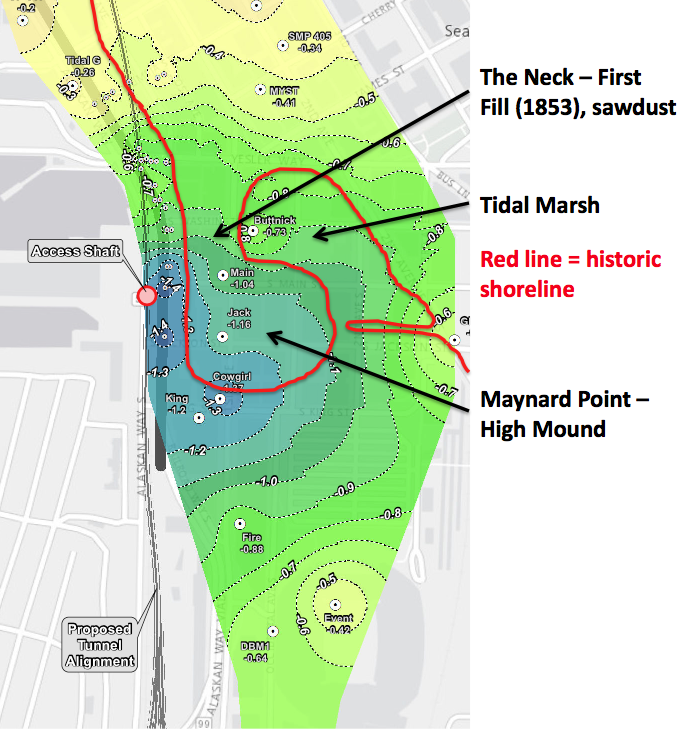

Below is a zoom in on the map, where I have added an outline of Seattle’s historic shoreline in red. You can clearly see that the areas of greatest settlement correspond to where the city was filled in around what is known as Maynard Point. (Also known as Denny’s Island, but this is a made up name that probably didn’t come into existence till the 1960s.) Maynard Point was a mound that rose perhaps 20 feet or so above sea level. It connected to the main part of Seattle by The Neck, a low spot that would periodically be covered by tides, converting the mound into an island. The Point has also been buried by fill.

Ever since WSDOT released information last week about their groundwater problems, people have been in a tizzy about the ground settling. Pioneer Square has had groundwater and settling problems for decades. Why do you think the sidewalks tilt? They weren’t built that way. Why do think so many buildings have steel retaining rods sticking out of them? They do because the ground is settling. Why do buildings have sump pumps, which are needed more often in the winter during high tides? The Seawall doesn’t stop the tide; it’s not supposed to either. Why do parking lots undulate? Cores show that under the surface is a stew of crap, including coal, lumber, pilings, wood debris, sawdust, ceramics, sand, boulders, charcoal, ash, bricks, metal, glass, that continues to decay, compress, and settle.

Or walk along Western Avenue between Yesler and Columbia. It looks to be an engineer’s nightmare. The middle of the street is higher than the sides and the entire road surface undulates. The concrete curbs also look as if they had been poured by a drunkard, sometimes disappearing under the street and sometimes rising eight to ten inches above it. Near the southern end of the street is a low point that every time I have walked by is a pool of water.

In 1996, the Washington state Department of Transportation (WDSOT) drilled a core nearby as part of a seismic vulnerability study of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. In the first four feet of the core, the drillers found three inches of asphalt, three inches of railroad ballast, or gravel, 12 inches of concrete, and 18 inches of broken concrete, pieces of creosote timber debris and rounded gravel. The technical report then lists organic soil and “a void from 4.0 ft. to 8.0 ft” before hitting moist, loose soil again. Fourteen and a half feet down the core changes to pieces of creosote timber and a new feature, an aroma of rotten egg and sulphur. The remaining 8 ½ feet of core is described as contaminated organic soil. A final note adds “See samples at own risk.”

Ask any building owner or tenant in the area and I suspect they will be able to tell you additional stories of how their building is anything but immobile.

I am not writing this to defend WSDOT, (I am not a Bertha booster), but no one should be surprised by ground surface and subsurface issues in this area. It certainly looks like Bertha has contributed to the problem but it does not bear sole responsibility. These problems are the legacy of the landscape where we live and that we have altered continuously since first settlement. And there is no end in sight…to the alteration and to the settling.