The Black River is Seattle’s most infamous river, or more accurately, lost river. The river was only about three miles long but was critical to the early history of the city. It was Lake Washington’s lone outlet and hence lone access point for boats traveling from the salt water of Elliott Bay to the fresh water of the lake, a route replaced in 1916 by the opening of the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the Lake Washington Ship Canal. (The canal officially opened on July 4, 1917, but the canal and locks had been completed in 1916.)

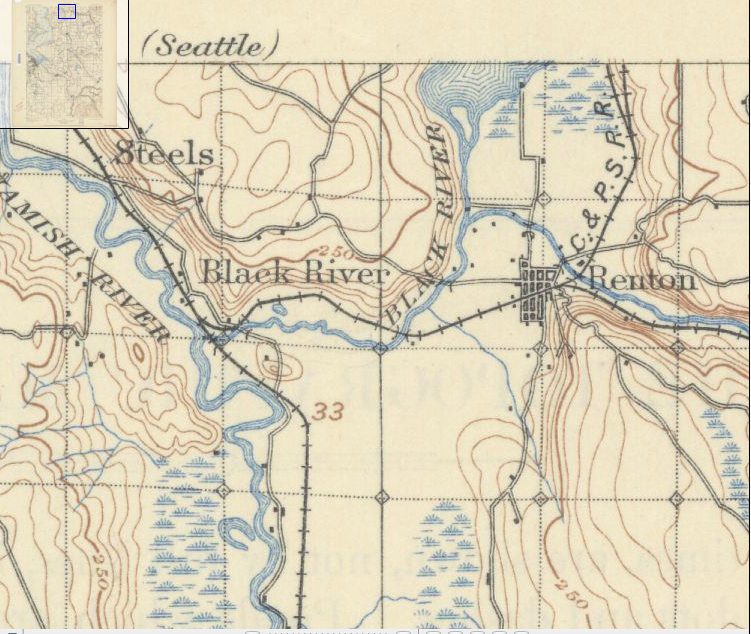

As you can see from the accompanying map, the 1909 USGS Topographic map of the Tacoma quadrangle, the Black flowed out of the lake near Renton, and was almost immediately met by the Cedar River, coming west out of the Cascade Mountains. The Black then wound around low hills, under the Columbia and Puget Sound RR, and met the Green River, where now became the Duwamish with the addition of the Black.  Historically, the Green River flowed into the White River in Auburn, and the two continued as the White to the confluence with the Black. Floods in 1906, however, changed the course of the White, which now drained, and still drains, into the Puyallup River. The Green kept its course and now became the outflow for the Black, until the disappearance of the Black in 1916, which is why the Green changes name for no apparent reason and becomes the Duwamish.

Historically, the Green River flowed into the White River in Auburn, and the two continued as the White to the confluence with the Black. Floods in 1906, however, changed the course of the White, which now drained, and still drains, into the Puyallup River. The Green kept its course and now became the outflow for the Black, until the disappearance of the Black in 1916, which is why the Green changes name for no apparent reason and becomes the Duwamish.

The Black’s name came from sediment washed out of the Cedar’s old river terraces. The White was significantly clearer. The Cedar gave the Black a second name. When the latter flooded it reverse the flow of the Black and pushed it back into Lake Washington. This is the origin of the name for the Black in Chinook jargon, Mox La Push, or “two mouths.”

King County’s first sawmill outside of Seattle was at the confluence of the Black and Cedar rivers. Started in 1854 by Henry Tobin, Joseph Fanjoy, and O.M. Eaton, it had two circular saws. In order to operate the mill, the trio built a six-foot high dam. Unfortunately for the men, the mill did not last long; the Black was too windy for transport. It was not too twisted though for vessels.

Soon after the discovery of coal near what is modern day Issaquah, a variety of people were “engaged in wordy discussions of the quickest and best way to render the Squak coal mines available,” noted The Seattle Gazette in February 1864. In floated William Perkins, who built a boat, floated and paddled to the mines, and returned with a full load. The 140-mile-long trip via the Duwamish and Black rivers and across Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish and back took him 20 days. Trips up and down the riparian highway eventually became easier as river travelers dredged sand bars and cleared out stumps and overhanging vegetation.

But everything changed in 1916, when Lake Washington was connected to Lake Union, which lowered the level of the larger lake by nine feet. This was enough to drop the lake below its historic outlet and the Black River slowly died, with remnants persisting until at least 1969. A photograph shows a narrow swath of shrubs, weeds, and cottonwoods that curved east between North Third and Second Streets toward the intersection of SW Sunset Boulevard and Rainier Avenue South. That last vestige of the Black now lies under the parking lot of a huge Safeway.

The other remnant of the river still exist. At its confluence with the Duwamish is the Black River Riparian Forest. Not the most beautiful of spots but following years of restoration, visitors have reported over 50 species including salmon, coyotes, salamanders, and bald eagles. The area also supports the largest heron rookery in the region.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.