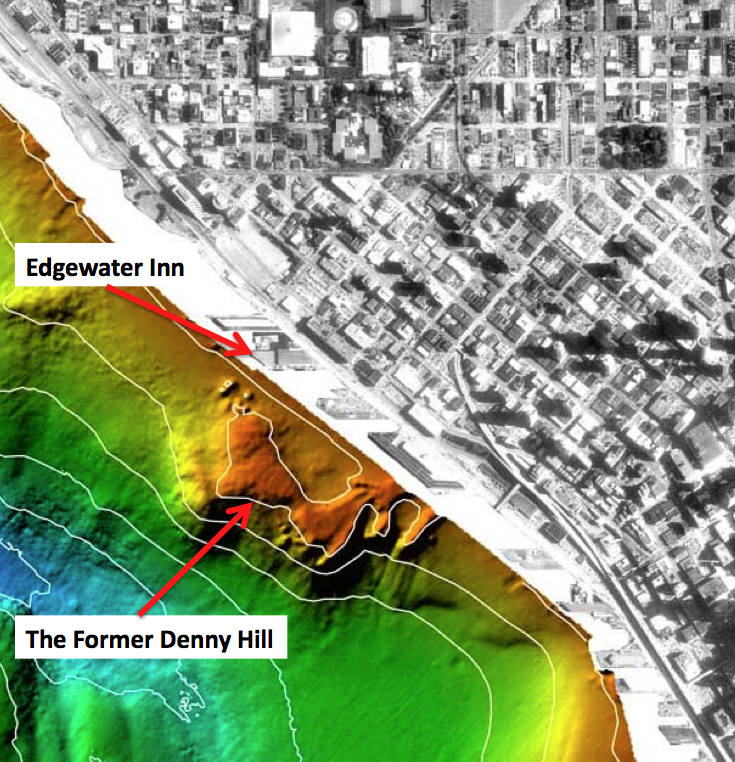

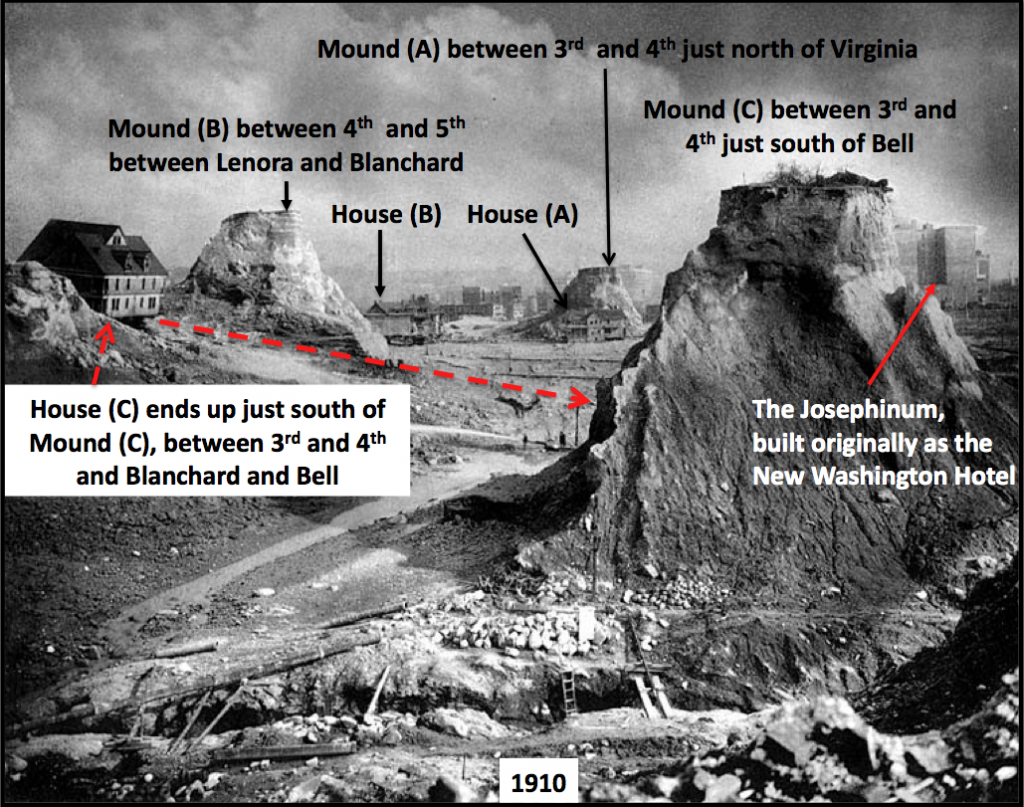

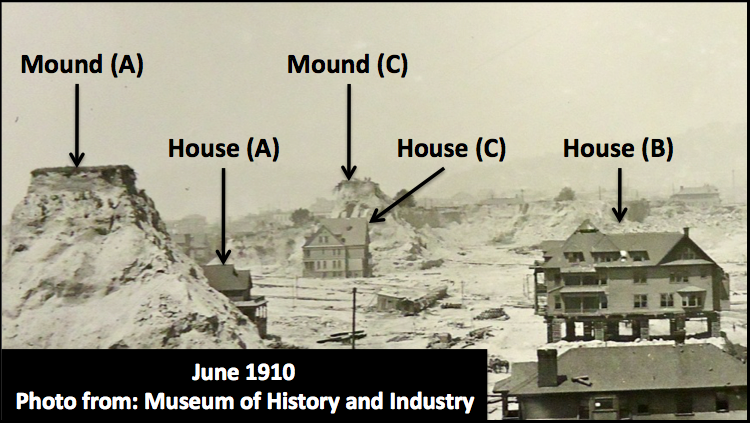

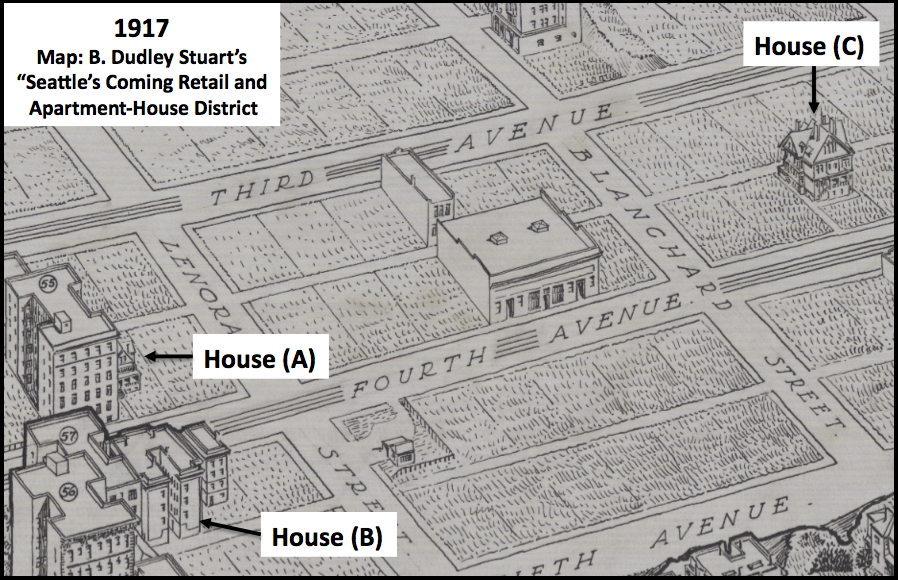

As a follow up to my post about my book cover, I want to provide some information about the houses in the photograph. Asahel Curtis took the most famous photograph of the regrades of Denny Hill in 1910, during what many call the first regrade of the hill but was actually the fourth regrade. The large Monument Valley-like towers are what are known as “spite mounds” or “spite humps,” which were supposedly owned by people who didn’t want to sell their property during the regrade. This is incorrect. I address this topic in the book.

Here’s information on the houses.

House (A)

- 2025 Fourth Avenue, property owned by Jasper Hoisington, who lived there with his wife, Nancy, as early 1901.

- At the May 28 1909, Board of Public Works (public entity to whom land owners apply to move a building) meeting, J.C. Hoisington applies for permit to move house from 2025 Fourth Avenue to NW corner of 5th and Virginia and then to move it back following the regrade.

- June 1919 – Musicians Association buys land.

- 1937 – Building leveled.

- New building erected, General Tire and Battery, owned by Musicians Club, which continue to own the property to this day.

House (B)

- Property at 2018 Fourth Avenue, Mark Michelsen builds apartment building in 1903.

- June 25, 1909 – Moving company Spear & McCoy applies to Board of Public Works to move house at 2018 Fourth Avenue two lots to the south.

- Sometime between 1910 and 1912 – Ornamentation of house stripped, with new first floor inserted under the house. Now known as Michelsen Apartments

- Leveled in 1956.

House (C)

- Originally at 2134 Fifth Avenue, SE corner of Fifth Avenue and Blanchard Street.

- Owned by Roger S. Greene, who apparently purchased property in 1890-91 and built a house on it in 1892.

- February 3, 1907 – Edward W. Comyns, working for Archibald and Cox buys SE corner of Fifth Avenue and Blanchard Street for $35,000.

- February 8, 1910 – Gustave Havers (I don’t know what the relationship was between Havers and Comyns and why Havers was able to move this house) gets permit from Board of Public Works to move house at 2134-6 Fifth Avenue to 2215 Fourth Avenue.

- 1914 – Property listed as Bell forth Apartments, which eventually becomes Lee Apartments at 2217 ½ 4th, owned by S & R Realty.

The Josephinum still stands. It is now low income housing and his owned by the Catholic Housing Services of Western Washington.

Material for for this story comes out of research for Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If interested, you can follow me @geologywriter on Twitter.