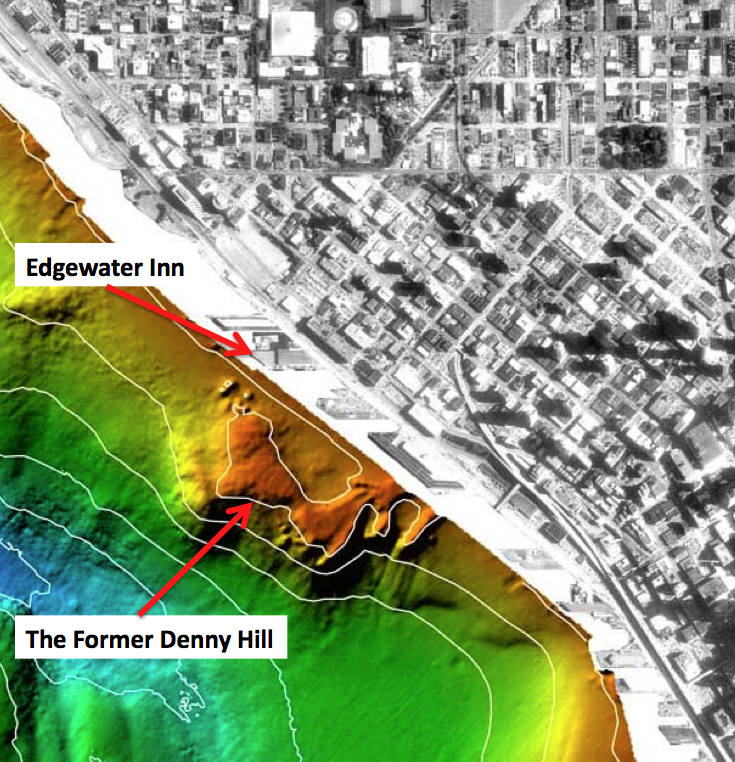

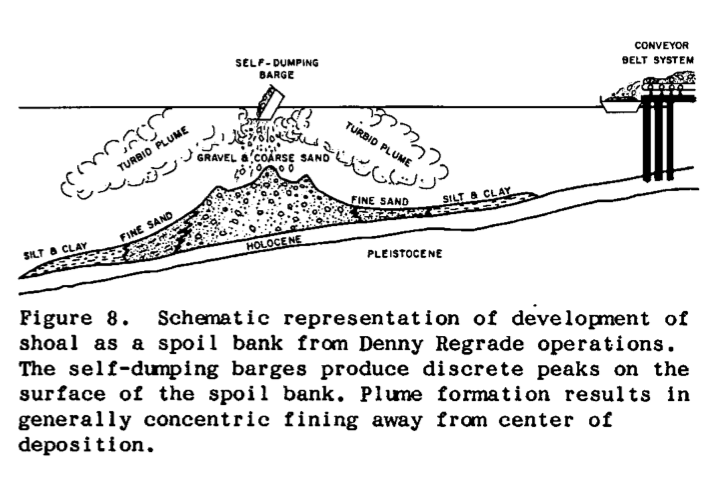

In my first technology post, I looked at the pile driver. I would now like to turn to an even less-heralded but rather fabulous piece of equipment, the self-dumping, reversible barge. They were critical to the final, 1928-1930, regrade of Denny Hill. Designed by naval architect William C. Nickum, the barges were used to tow dirt from the regrade out into Elliott Bay. Each cost $15,000 and was built by the Marine Construction Company. They were named the C.C. Croft and N.L. Johnson, after tugboat captains.

The barges were the same top and bottom with an open deck and two watertight chambers, or tanks, that extended the length of the barge between the decks. Each barge could carry about 400 cubic yards of dirt. To fill a barge, a tug nudged the barge under a chute built on a dock over Elliott Bay.

The tug then towed the loaded barge into the bay, where a crew member pulled a rope that opened a valve in one of the chambers. Within three minutes, water filled the tank, and the out-of-balance barge flipped over, dumping its load. No longer weighted down by the dirt, the barge rose high enough to drain the internal tank, which took about eight minutes. The tug returned the barge back to shore, ready for its next load.

The barges, or the barge workers, did not always perform as planned. In September 1929, one barge smashed its mate causing it to sink. Three weeks later, after both barges were repaired, workmen left the seacocks open on one, which caused it to flip and hit its tug, which promptly sank. And finally a week later, the remaining barge flipped while at dock, damaging the dock and scow, both of which were put out of service, forcing the entire regrade project to shut down for several days. Tug drivers also had the problem of the barges disappearing in foggy weather, which caused delays. Still the self-dumping, reversible barge was an amazing piece of early Seattle technology.

All images are from Seattle Municipal Archives.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.