David Swinson “Doc” Maynard was one of early Seattle’s more colorful characters. In his wonderful history of Seattle, Skid Road: Seattle and Her First Hundred Years, Murray Morgan writes of Maynard: “Maynard was a man of parts, a warm human being whose worst faults grew out of his greatest virtue, his desire to be helpful; and few people ever got into more trouble trying to help others.” One of those ways in which he tried to aid others, and for which it appears he did not suffer, was in the field of potatoes.

Writing to the editor of Olympia’s Pioneer and Democrat newspaper, in November 1858 from “Alki Farm, King Co., W.T.,” which we now know of as Alki Point in Washington State, née Territory, Maynard described his new life away from the urban chaos of Seattle. “Having recently embarked in the Agricultural Ship called Farmer, I wish to see her float with the tide of prosperity and progress.” What made Maynard’s endeavor at cultivation unusual, he thought, was his use of a novel fertilizer.

The previous year he had gathered one small canoe’s worth of kelp, which he cut into small pieces and placed on his recently sowed field of spuds. When he harvested his kelp-enhanced spuds, he found a yield of 27 pounds per hill, compared with his previous year’s crop of just 4 to 5 pounds per hill. Truly astounded and pleased by his process as a potato whisperer, he sent part of his crop to the editor urging him: “Try them baked, and give me your opinion of them.”

Maynard was hardly alone in recognizing the potential of kelp. In 1913, soil scientist Frank Cameron wrote “from time immemorial sea-weeds have been recognized as having important manurial value.” Nor was Maynard the last to try to exploit kelp in Puget Sound.

Prior to World War I, Germany had been the world’s most important supplier of potash, which was rich in potassium. After the war began, and the supplies of potash dwindled, scientists around the country began to seek out a new source and found that few products were better than kelp, which could be burned to potash, and few places richer in kelp than Puget Sound. With a potential market of millions of dollars, six companies planned on developing kelp-to-potash plants on the waterway.

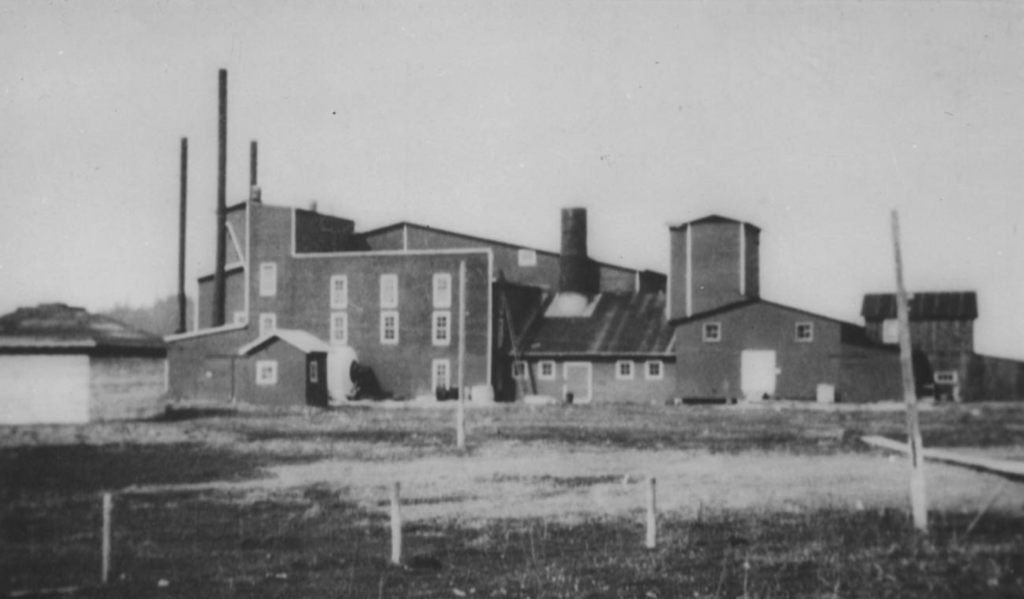

At least two plants opened. The Pacific Products Company completed a plant in Port Townsend and Western Algin Company did the same at Port Stanley on Lopez Island. Neither of them were terribly successful. When the war ended, Germany began to resupply the world with potash, and kelp was left to grow unmolested in the waters of Puget Sound.