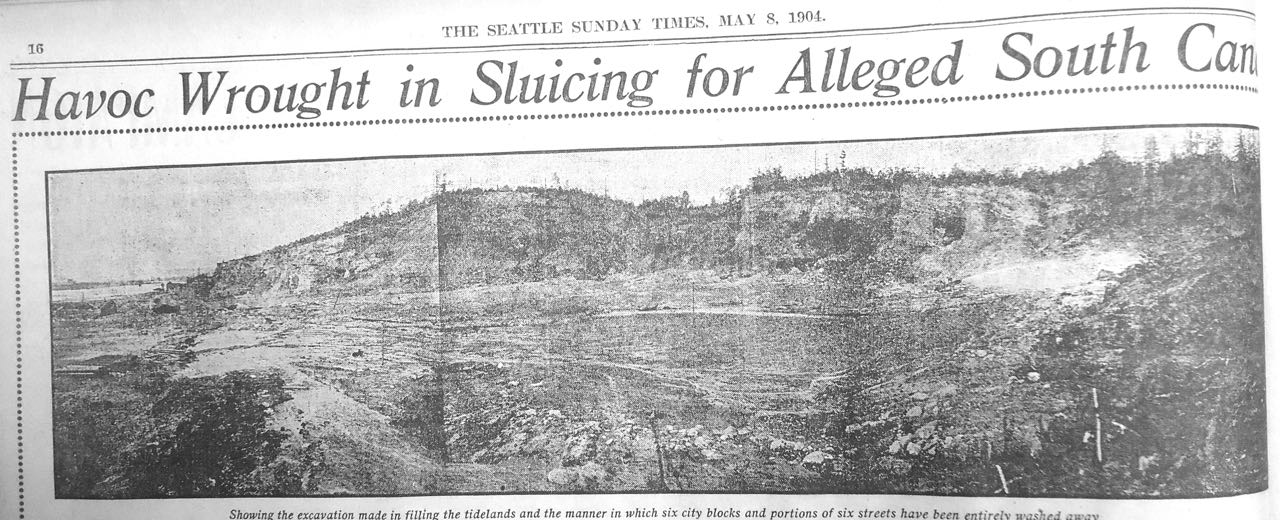

Of all the crazy schemes that didn’t come to fruition in Seattle, the South Canal through Beacon Hill is one of my favorites. Unfortunately, I know of only one photograph of it and it’s not very good, but I have decided to look at it anyway. (Just wish I knew how to make provide one of those magnifying things so it can be looked at more closely.) As I noted in a previous post, little of the South Canal was built. Here is that story.

The hill-cutting phase of the project had begun in February 1901, when Eugene Semple acquired rights to surplus water from the city’s new water source, the Cedar River. Built as a response to the lack of water to put out the Great Fire of 1889, the new system brought water from the Cedar River to reservoirs atop the city’s hills. Semple’s plan was to take advantage of the elevated reservoir on Beacon Hill by tapping into it via wood stave pipes. Water from Beacon Hill would drop nearly 300 feet down to the base of the hill. As the water plunged down slope, it would enter narrower and narrower high pressure steel pipes, which would increase the water pressure to the point that the water shot out with enough force to dislodge soil, rocks, and boulders.

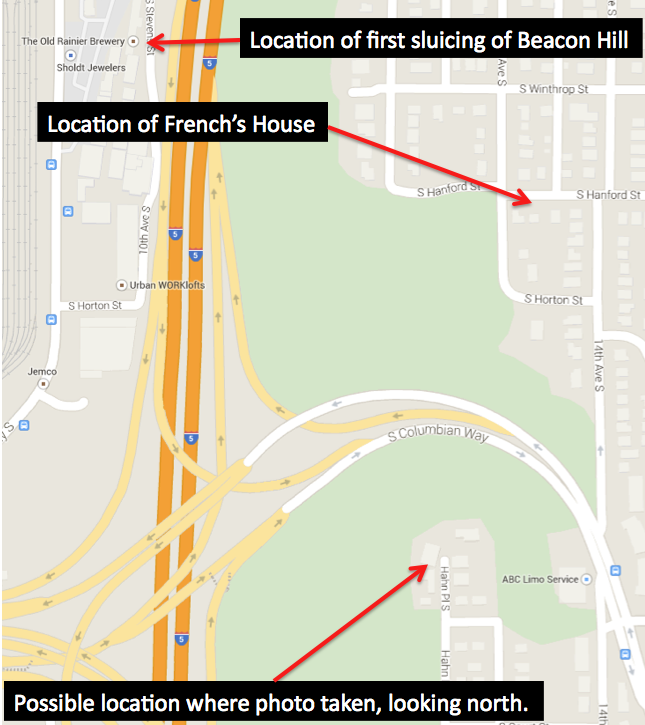

On November 14, Semple’s crews began their attack on the western edge of Beacon Hill, directly east of the Bayview Brewery at 10th Ave S and Hanford Street. Everyday the crews blasted the hill with 14 million gallons of water, which created about 2,000 cubic yards of fill that flowed in flumes out into the Duwamish River’s tideflats. The first area filled was just north of the brewery, where the Washington Iron Works and Frye-Bruhn Meat Packing Company would be able to replace their old pile-supported buildings with new structures built on the new land.

By late 1904, the hydraulic giant had blasted away enough of Beacon Hill to create 52 acres of solid land along the hill’s western edge. But not everyone was happy. Philip and Maria French filed a petition with the city council seeking an award of $6,000 for damages to their home. The couple lived atop Beacon Hill, at 14th Avenue South and Hanford Street. Originally built more than 700 feet from the edge of the hill, the house and surrounding property were now just 30 feet north of a 100-foot-high sheer cliff created by Semple’s hydraulic cannon. Amazingly, the French’s lost their case.

Wielding a bit of hyperbole, the Seattle Times reported that “without authority and unknown to the public,” Semple’s crews had washed away seven streets of Beacon Hill, creating the “great hole” adjacent to the French’s property. The resulting damage suits against the city, added the Times, were piling “up so high that the corporation counsel is unable to see over them.” In contrast, real estate agents didn’t understand the Times’ concerns. Henry Dearborn noted that that “it is certainly good business ethics” to sluice down less valuable lands, such as Beacon Hill, in order to create more valuable land below.

With all of the bad publicity, Semple’s plan was doomed. By the end of 1904, the city council had voted to stop Semple’s use of Cedar River water. Eventually weeds started to grow in the chasm that was to be the South Canal and the project became another example of Seattle’s failed attempts at creating a new transportation corridor.

The chasm still survives. Have you ever wondered why the Columbia Way off ramps from I-90 go up to Beacon Hill where they do? It’s because the I-5 engineers took advantage of Semple’s folly, which provided a nice access point up to Beacon Hill.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.