Recently I was standing atop Pier 66 along the Seattle waterfront considering another central tenet of the city’s urban mythology, which is that Denny Hill no longer exists. Conventional wisdom holds that our forefathers eliminated the high mound north of downtown to make way for the coming tide of business. This is not entirely true. Denny Hill still stands; you just need to know where to look. Ask UW oceanographer Mark Holmes and he can show you.

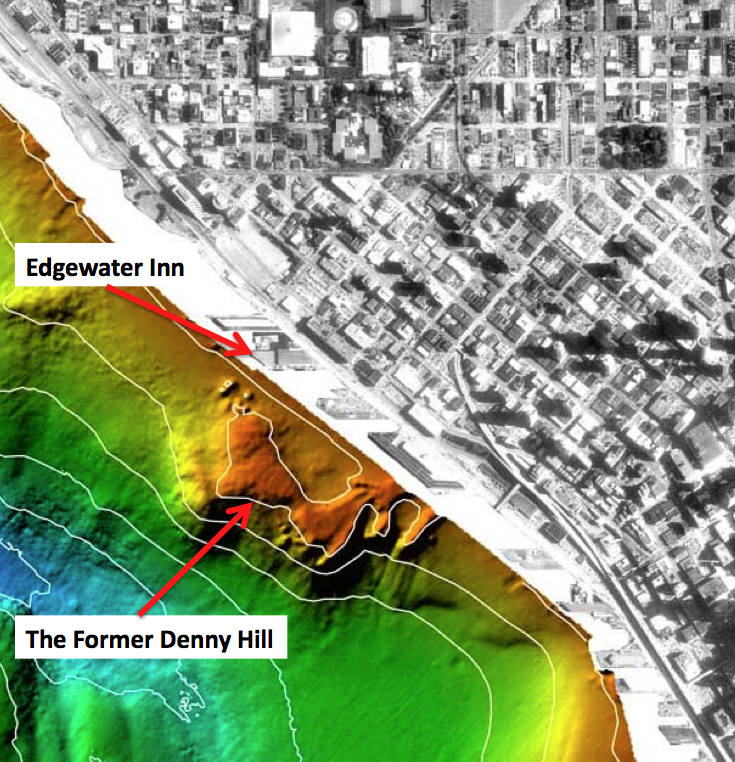

In the summer of 1988, Holmes and two colleagues decided to examine the seafloor of Elliott Bay. The trio wanted to better understand sedimentary processes and their relationship to human made changes in the bay. The earliest map they consulted, an 1875 hydrographic chart, showed that close to shore the seafloor dipped gently and uniformly. When they looked at a map from 1935, they found that the moderate slope was gone, replaced by a shoal, or linear landform “unlike any natural feature” typically found in Puget Sound, says Holmes. The center of the mound was about 500 feet offshore between the Bell Street Pier and the Edgewater Hotel. (Loeffler, Robert D., Mark L. Holmes, Richard E. Sylwester, “In Search of the Denny Regrade: Fate of a Large Spoil Bank in Elliott Bay,” Puget Sound, Oceans ’89 Proceedings, 1989, pg. 84 – 89.)

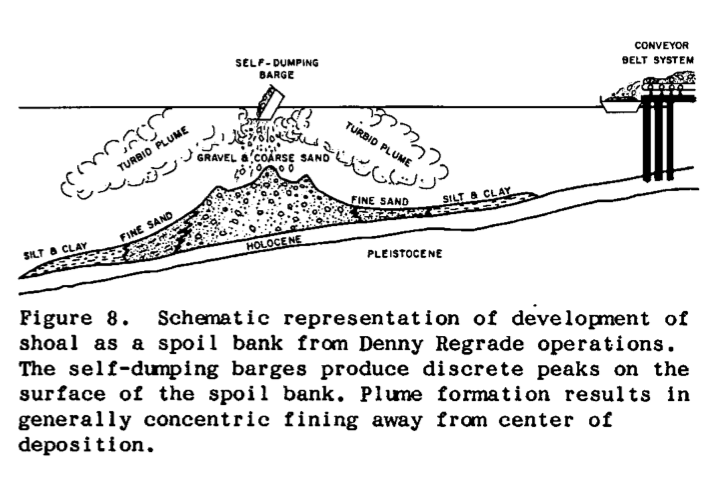

Hoping to better understand the anomalous landform, Holmes’ team sailed into Elliott Bay on the research vessel Coriolis to run what is known as a seismic reflection survey. Widely used by geophysicists and oceanographers, the technique utilizes sound waves to take a snapshot of layers of underwater, or underground, rock. When the energy pulses bounced back, an array of detectors recorded the data and generated an image of the shoal’s surface and subsurface.

The seismic reflection data revealed a hummocky top, punctuated by an odd, flat-bottomed summit depression. Internally, the shoal consisted mainly of coarse sand and gravel with flanks of clay and silt that sloped steeply to the west. It ranged between 10 to 120 feet thick, measured 1,500 feet wide by 2,500 feet long, and contained an estimated 8.9 million cubic yards of sediment.

The mound’s shape and texture made Holmes suspect that it was the product of dumping, which the Army Corps of Engineers does regularly into Elliott Bay with sediment from the Duwamish River. Such spoils, however, normally go into deeper sites, where contaminants would have less impact on marine wildlife. As Holmes and his team began to further research the history of Elliott Bay, they realized that they had discovered something more unusual. They had “stumbled into the Denny Regrade” story, says Holmes.

They learned that most of Denny Hill, the high mound that had stood at the north end of downtown and which was leveled between 1898 and 1931, ended up in Elliott Bay, carried out by a sluice during the initial periods of regrading and later by self-tipping barges. Conspicuously, the total sediment removed from the hill corresponded to within ten percent of the shoal’s volume. Holmes’ team accounted for the difference by landslides on the steep faces, which carried material deeper into the bay. And the odd summit flat spot? Apparently a boat had run into the mound, and dredgers had had to go out into the bay and flatten the boat-damaging, high point.

In Holmes’ mind, they had clearly found the long forgotten remains of Denny Hill. After more than a half century, the famous mound had been rediscovered. It had not been eliminated, it had just been displaced.

I know it’s a bit of a stretch to write that Denny Hill still stands but the submarine mound in Elliott Bay is the lone topographic remnant of the famous knoll that formerly stood at the north end of downtown Seattle. By rediscovering the regraded hill, Holmes and his fellow researchers have provided a direct link to Seattle’s greatest attempt to better the city through reshaping its topography.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

Is it also true that Myrtle Edwards park consists of the dirt from the I-5 “ditch” through downtown Seattle? Where did the Dearborn cut end up – in SODO?

Great article! Thanks!

Bob, Thanks for your note. I don’t know about what makes up Myrtle Edwards. I will see what I can find. Regarding the Dearborn cut, yes, it did end up out on the tideflats. Not sure exactly where but I believe just west of Dearborn. By the way, that is the regrade with the deepest cut of any, about 130 feet. David

David:

When I walk or drive around any of Seattle’s hills, it’s apparent that all of these hills are essentially terraced to create level streets. Was that a major engineering feat? Where did all of that soil go?

Gary

Gary, good question. I refer to this type of change as a little “r” regrade, as opposed to the capital “R” Regrade, such as the Denny Regrade. You are correct that street regrades were wide-spread throughout Seattle, and probably most cities. I have not investigated these because there are so many. I assume that most of the soil that was moved went to side lots or to fill in low points on streets. What surprises me is when you come across streets that have been terraced into two levels. I can think of several of these on Queen Anne and in Madrona. I wonder why these ended up this way? Lots of questions out there.

Cheers,

David